By John Brinsley, Aikido Daiwa

“The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

The above phrase originates from a  sermon by American transcendentalist and Unitarian minister Theodore Parker (1810-1860) and was made popular by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Parker, a fierce abolitionist, saw the end of slavery as inevitable, based on his faith in “a continual and progressive triumph of the right.”* He conceded that it might be hard to ascertain merely from personal experience when and how justice would prevail. Yet instinctually he knew it to be true and saw it as his duty to fight for abolition. Along with organizing resistance to fugitive slave laws, Parker also advocated for other mid-19th century reform movements, including women’s rights and income equality.

sermon by American transcendentalist and Unitarian minister Theodore Parker (1810-1860) and was made popular by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Parker, a fierce abolitionist, saw the end of slavery as inevitable, based on his faith in “a continual and progressive triumph of the right.”* He conceded that it might be hard to ascertain merely from personal experience when and how justice would prevail. Yet instinctually he knew it to be true and saw it as his duty to fight for abolition. Along with organizing resistance to fugitive slave laws, Parker also advocated for other mid-19th century reform movements, including women’s rights and income equality.

Similarly, King viewed the civil rights struggle as ultimately being successful despite the obvious and sometimes crushing presence of evil and despair in the world. He preached that truth could not be suppressed forever; there was something in the human condition that sought freedom and equality and could overcome unjust laws and conditions. This faith, deeply rooted in Christian theology and Western philosophy, helped sustain King and his followers as they fought against hatred and violence that only worsened in reaction to their movement. Non-violent resistance took the kind of courage that 50 years later seems almost unimaginable, except when considering that the alternative was even more so.

It is important to stress that both Parker and King saw the inevitability of justice as a reason to advocate, not as a palliative for acceptance and inaction. Not for them the passive acceptance of a divine plan; progress could not be achieved by words alone. It required commitment, toil and sacrifice to resolve conflict and lay the groundwork for eventual success, even if it wasn’t realized within their lifetimes.

Parker did not live to see the outbreak of the Civil War, though his work contributed to the death knell of slavery. King was constantly and presciently aware that he was unlikely to live long enough to see the fruits of his labor. “I’ve been to the mountaintop,” he preached in a sermon in Memphis on April 3, 1968. “And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you.” The next day he was dead.

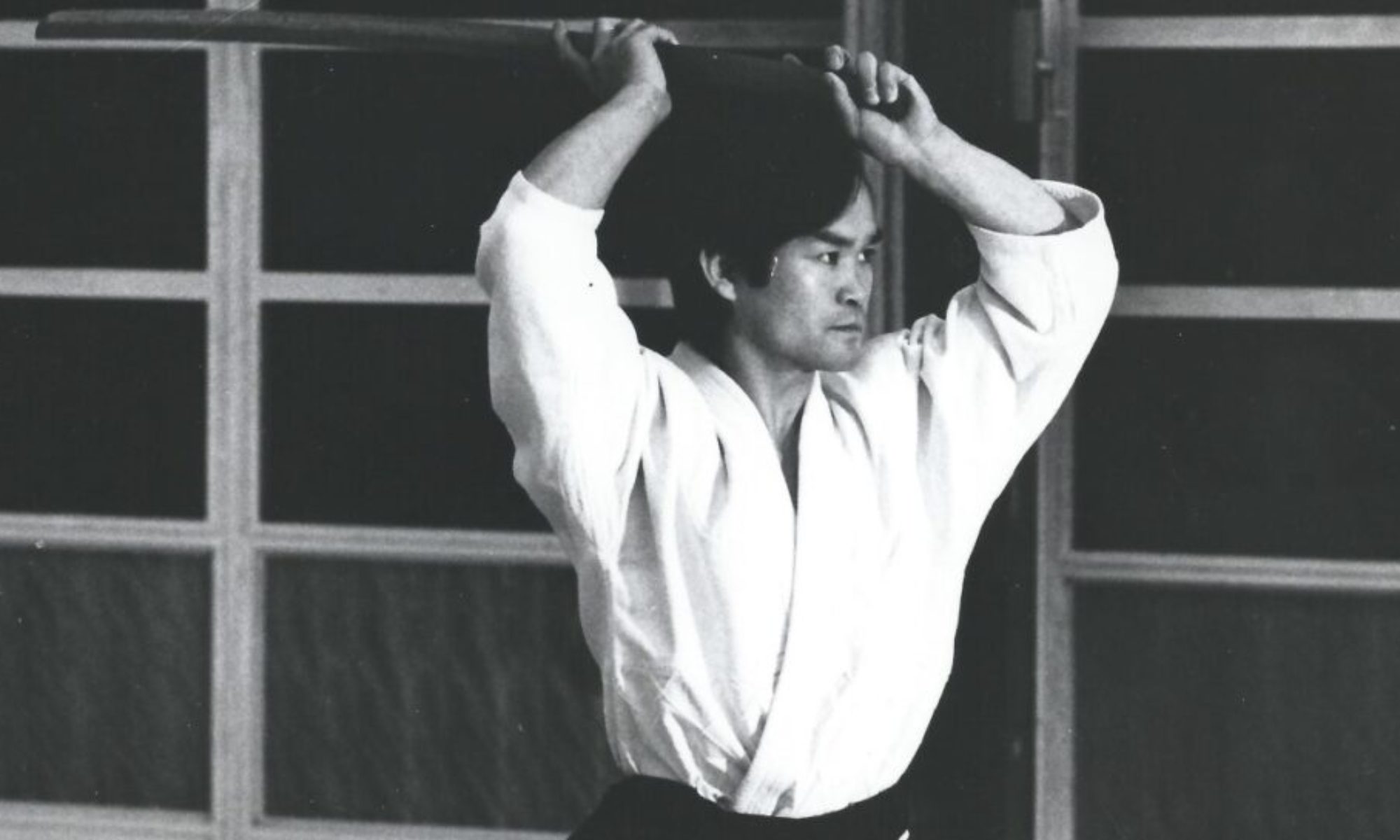

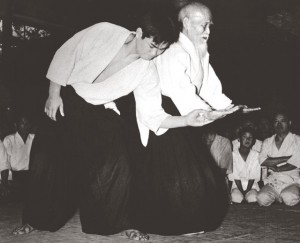

In the month that we commemorate King’s life, it is worth reflecting on the 21st-century application of Aikido, created by a man born in the 19th century who nonetheless lived for more than a year after King’s assassination. Morihei Ueshiba’s expression that “Aikido is Love” reflected a state of insight attained after arduous training in budo and devotion to the mystic roots of Japanese religion. The statement reflects a personal realization that can serve as a motivation or exhortation for others to follow, and underlines the principle of Aikido as a universal means to confront and resolve conflict. Rather than being an expression of ego, it is instead an expression of harmony.

Achieving that ideal requires day-to-day examination of technique and how it is applied: giving and receiving, friction and acceptance, fear and reward. It is not a matter of only believing in the precepts and philosophy of Aikido; it must be forged on the mat with yourself as your biggest rival, overcoming your own limitations.

This requires faith and commitment that practice (keiko) will result in intended and perhaps unintended benefits. It isn’t easy day after day, year after year, to work on technique only to discover that there is much more to work on. Other aspects of life also command attention and take priority. It is easy to be distracted by day-to-day events, both important and otherwise. Fatigue plays its part, as does injury, and age. These build up, and can become real barriers to continuing keiko. But the rewards for perseverance are real.

Much like the arc of the moral universe, the path that Aikido provides is anything but straight. Given the chaos, misery and conflict that exist in the world, it is easy to dismiss that path as delusional. But it must be trod if we are to reach the mountaintop that King, and O-Sensei, both saw.

* As an aside, Parker in an 1850 sermon, called for a democracy “of all the people, by all the people, for all the people,” words that Abraham Lincoln appropriated for the Gettysburg Address.

Editor’s note: This post also appears on the blog of Aikido Daiwa.