Peregrine Morkal-Williams, East Lake Aikido

Adapted from a personal journal entry, written after an evening class when I had a bit of a migraine. I get both migraine and tension headaches, both thankfully infrequent, and both typically with slow onsets and a fairly long window during which I can make behavioral choices that either make it bad or make it better.

I started getting a migraine at work today, a slow onset over several hours, pre-empted by the decision to have a short nap on the couch in the hospital chaplains’ office library (i.e. fatigue) around 2pm and then an immediate red rig alert for cardiac arrest that I needed to attend to. Which meant, instead of a nap, I got to go engage with Chaostown (the emergency room). So I wasn’t too surprised when the migraine pattern coalesced—the pain never got severe, fortunately, or really ever more than a 4/10. Maybe more but only for blips. Right side of my head felt wonky, left side of head felt totally normal, I was craving salty food. The pain wasn’t pressure. Kind of an acidic or electric feeling, which I think in nerve cells are not that different, taking turns with numbness and pain. All familiar feelings.

I think when I walked into the dojo, I felt uncomfortable with the idea of intentionally going light. Part of me is more comfortable with pushing hard, seeing how much I can take, and hurting. I’ve done it before. But after my conversation with Sensei last weekend, I wanted to try a different approach. The pushing is part of a “feed the animal” training mode, which is often healthy and vigorous and life-giving. But we had talked about how maybe zazen is starving that same animal—which is also fruitful. In the car and when I got to the dojo, I was mentally framing my plan for class as “I will do my best and step off the mat if I need to.” I think “do my best” meant “push, but not too hard.” Not an easy balance!

At the dojo, it hurt to bow. (I still did bows, obviously, though shallower.) I was fine in weapons—once a migraine starts the main antagonists are moving my head around a lot, muscular exertion, and poor nutrition/electrolyte intake. Weapons wasn’t pain-free, but I wasn’t making anything worse, and didn’t have to put much intention into head-care.

When we got to body arts, I proactively asked each of my partners to train with me in a “slow and chill” manner, which they did. Sensei only had us do throwing/ukemi for one technique, and I said no to falling without trying it. That was a victory—normally, my habit is to try falling, say “well, I didn’t die,” and keep doing it even though it hurts and gradually makes my headache worse. Today I experimented with starving the animal, with not pushing.

And there’s a lot to learn, training light! I thought of it as Feldenkrais—light, but present, open, curious. Not muscling through anything because that would cause pain. So then I was thinking of migraine prompting me to feel for alignment by removing the option of muscularity. And then I thought of my migraine as a training partner. Realizing that migraine had something valuable to teach me helped me to find a posture of acceptance and kindness toward it. The metaphor of training partner is really helpful because I have been thinking about relationships with training partners a lot. Sometimes a training partner doesn’t do what you want them to do. And…that doesn’t change anything. You still have to meet them as best you can, be kind, be respectful, etc. You can’t control or try to control them. You can just be present with them and attend to your own learning, and accept that they will present lessons to you regardless of what you had in mind. All this is true of kohai and senpai alike, by the way. And all this is as it should be.

Anyway, when I called migraine a training partner out loud after class, I got that feeling of crying behind my face that tells me something holy is happening. Not as dramatic a feeling as it sometimes is, but I am pretty sure that’s what it was. The training partner metaphor is founded on acceptance of what is (i.e. migraine) and is a way of loving myself through that.

After aikido, my head felt about the same as it had before—victory. I drank some Gatorade, went home, had a burger and ice cream, and then stared at my phone for an hour and a half (which is typically quite good for my headaches because it keeps my head still). The migraine has cleared.

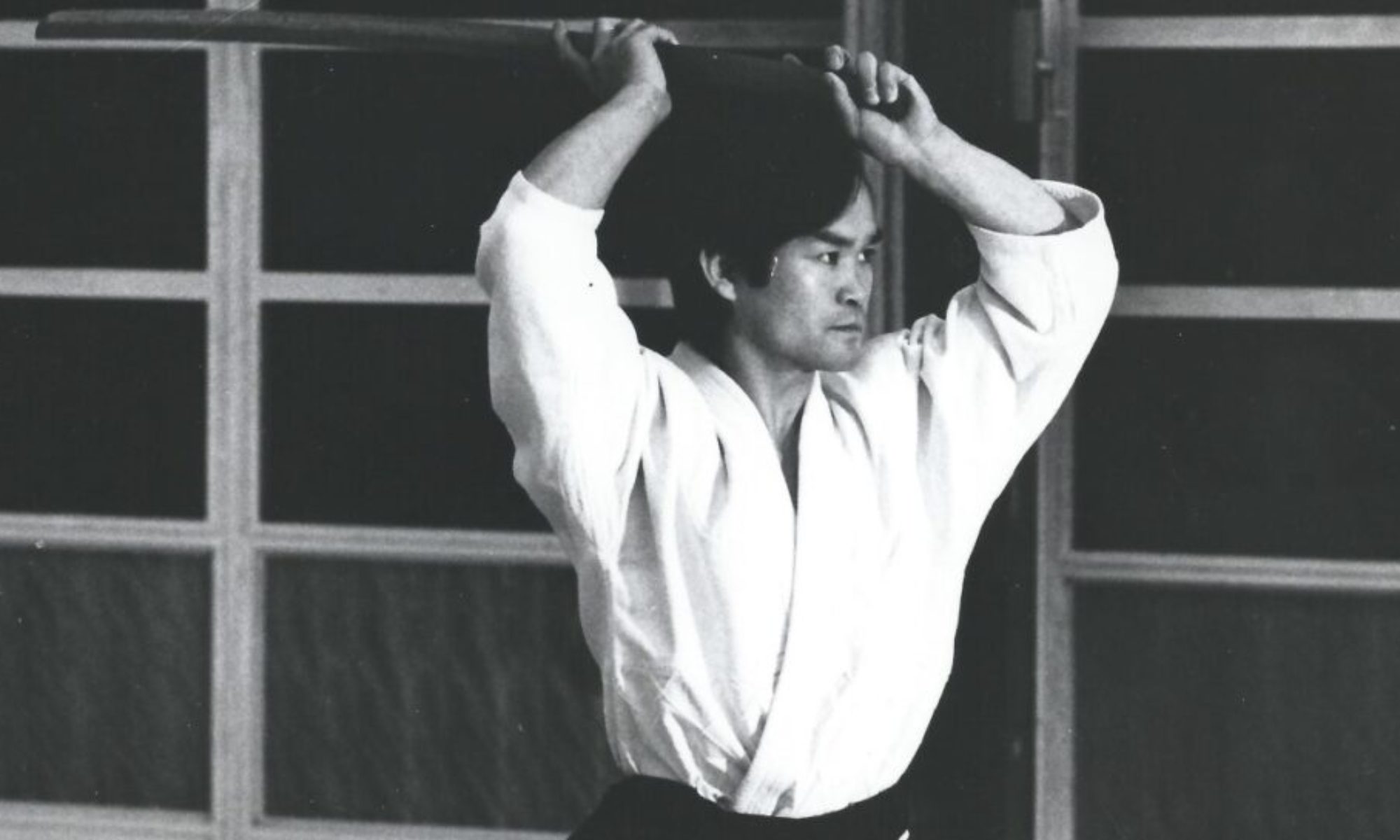

Peregrine Morkal-Williams, nage foreground.