Todd Fessenden

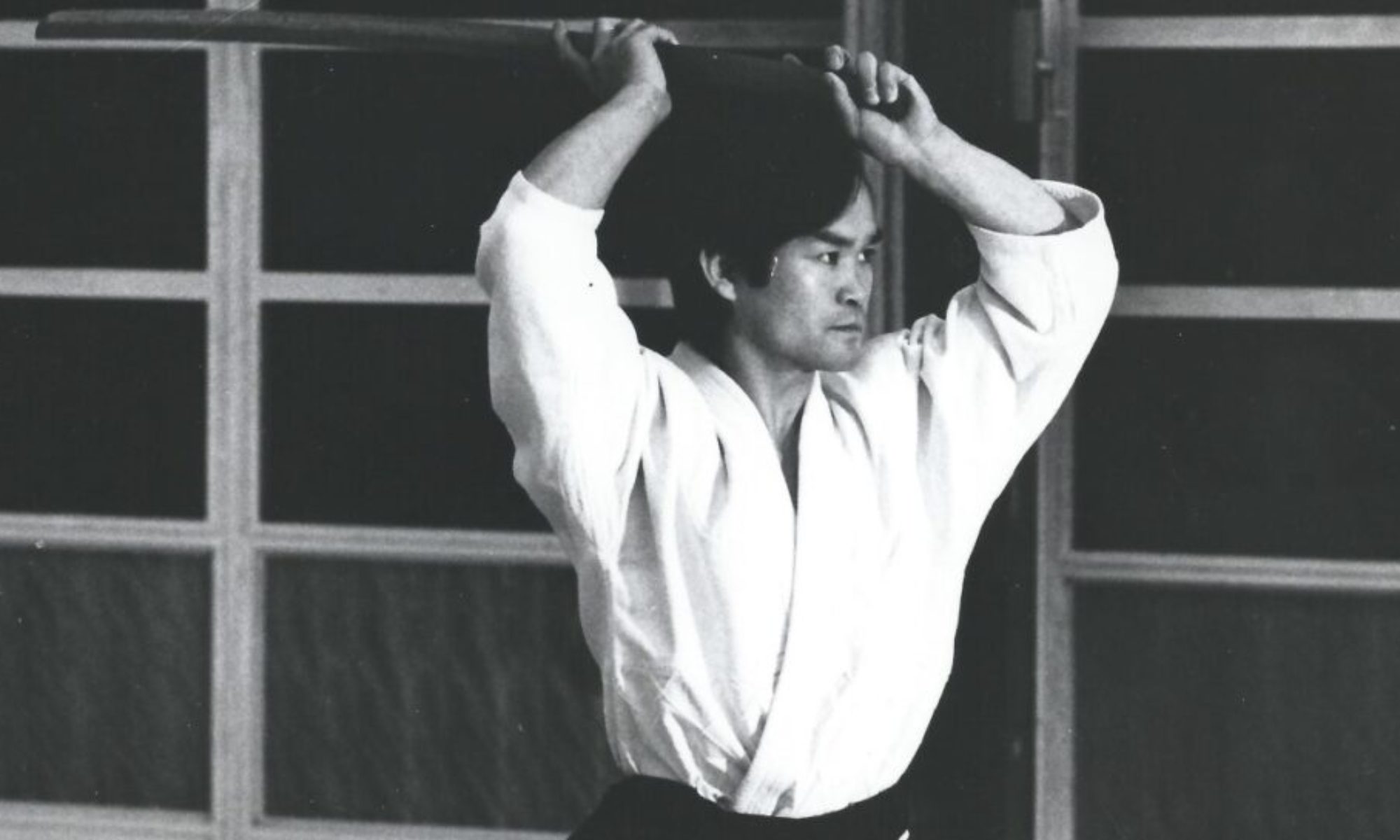

For a couple of seasons about 30 years ago, my teacher Nobuo Iseri Shihan and I were picking persimmons in the late fall. It so happened that Iseri Sensei had been supplying Mrs. Chiba with persimmons for some time, as persimmons grew abundantly in our little neck of the woods. Japanese pick and dry persimmons in the fall as an end of year tradition. In Japan these persimmons are called kaki, and once dried they are called hoshigaki.

Ironically, these fruits are only grown in a very specific climate zone, which happens to exist in Japan and also Southern California. Persimmons, particularly the large Hachiya persimmons, grew in the Ojai valley of California where Iseri Sensei and I both lived. If you haven’t had a dried Hachiya persimmon, or a ripe one for that matter, do yourself a favor and find one. They are sublime. Eaten before they are ripe, they are astringent and will immediately dry your mouth. Eaten ripe they have an almost jelly/mango-like texture and dried they have a light sugar coating which comes out at the end of the process. Only the Japanese could imagine such a out-of-this-world treat.

Fresh (right) and stages of drying (left)

On occasion Iseri Sensei would drop by and visit me at my home in Oakview, to check on me and the family. It was always an honor to see my teacher, and inevitably he would drop some knowledge on me as well. On probably his first visit to our home, he noticed the house across the street had a number of large persimmon trees, mostly Hachiya. He suggested we harvest the persimmons from those trees and send them to Mrs. Chiba in the fall. I asked the owner, a very old and frail man named Larry, if we could do so and he told me I was welcome to harvest as many as I like. There were so many persimmons that would just go to waste every year as these trees produced hundreds of persimmons. I thought we could certainly make this work.

So, for two seasons Iseri Sensei and I harvested persimmons. He taught me exactly how to cut the fruit from the tree so as to create a “T” in the stem to hang it from for drying and we meticulously packaged what was probably up to two hundred persimmons for Mrs. Chiba. Iseri Sensei’s sister, Kiyoko, also gave me tips on how to best prepare them for drying – dip them in vodka first! This was one of my most cherished times with my teacher. Iseri Sensei told me that I would be rewarded for my efforts and that we would get some dried fruit back. I saw it as fairly transactional, aside from the fact that we were supplying Mrs. Chiba, which felt pretty noble as we all held her in very high regard. We would send boxes of them to San Diego and sometime later, some dried persimmons came back and I think I received less than a half-dozen. I was disheartened. I felt like the benefit of all that effort, was not in line with the work! This too was a lesson I needed to learn.

I now dry persimmons every fall. Getting the actual fruit is the easy part, I can find them at a local Asian food market now. The roughly month and a half it takes to get them to their end point is a daily effort that requires attention to detail and consistency. Massaging the fruits with a firm but sensitive grip is more of an art than a science. Knowing when they are ready takes some experience. I now know why so few come back, and how much the process mirrors the development of students in Aikido and other Japanese arts.

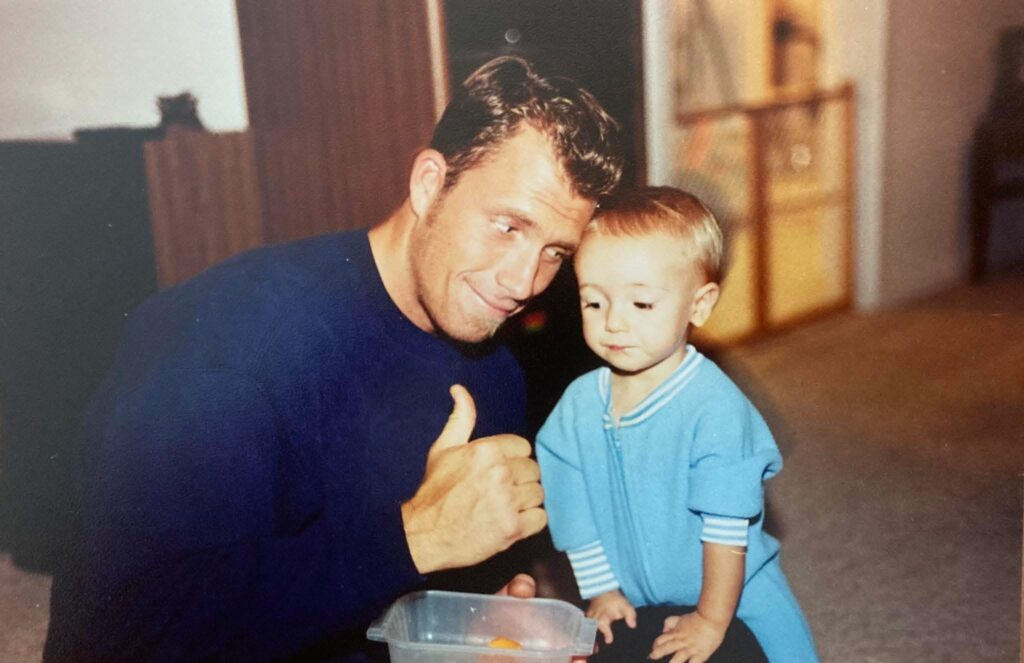

My best friend shared ripe persimmons with his god-son, my first son Charlie, when he was still a baby. Matt passed away in 1999, and this memory around persimmons is one of my most cherished memories of him. Matt was a warrior and a Navy SEAL, a brother to me and dedicated godfather.

Matt and Charlie eating persimmons 1998

I distribute my dried persimmons very carefully to close friends, sparingly. One of my dearest friends and mentor, a Goju Ryu Karate Shihan, had cancer about five years ago, and I shipped him the lion’s share of my stock that year because I knew that they had a high level of antioxidants and vitamins he especially needed. I still send him a few every year, even though he has fully recovered. This tradition that my teacher introduced me to runs deep in my family now, and in the most noble and meaningful ways. It is a treasure in its own right.

I now know the value of a single dried persimmon. I know the effort that Mrs. Chiba had to put into every single fruit, and the treasure that came back to me, similar to the effort each of our teachers puts into us. I also now understand the value of giving and giving back, and the commitment to doing something to the best of one’s ability – whether that be making hoshigake or refining your ikkyo, ukemi or approach towards life in general.

The real fruits of our labor sometime come in small bits, a little at a time, with lots of effort. Sometimes you do that on your own, and sometimes you have your teacher to walk you through it. Regardless of how you do it, it’s worth doing.

Hoshigake drying in Colorado

Thanks Todd

Thank you for sharing. Such a lovely story and metaphor.

干し柿一番好き

Editor’s note: the characters in the last comment read “ Dried persimmons are my favorite”!