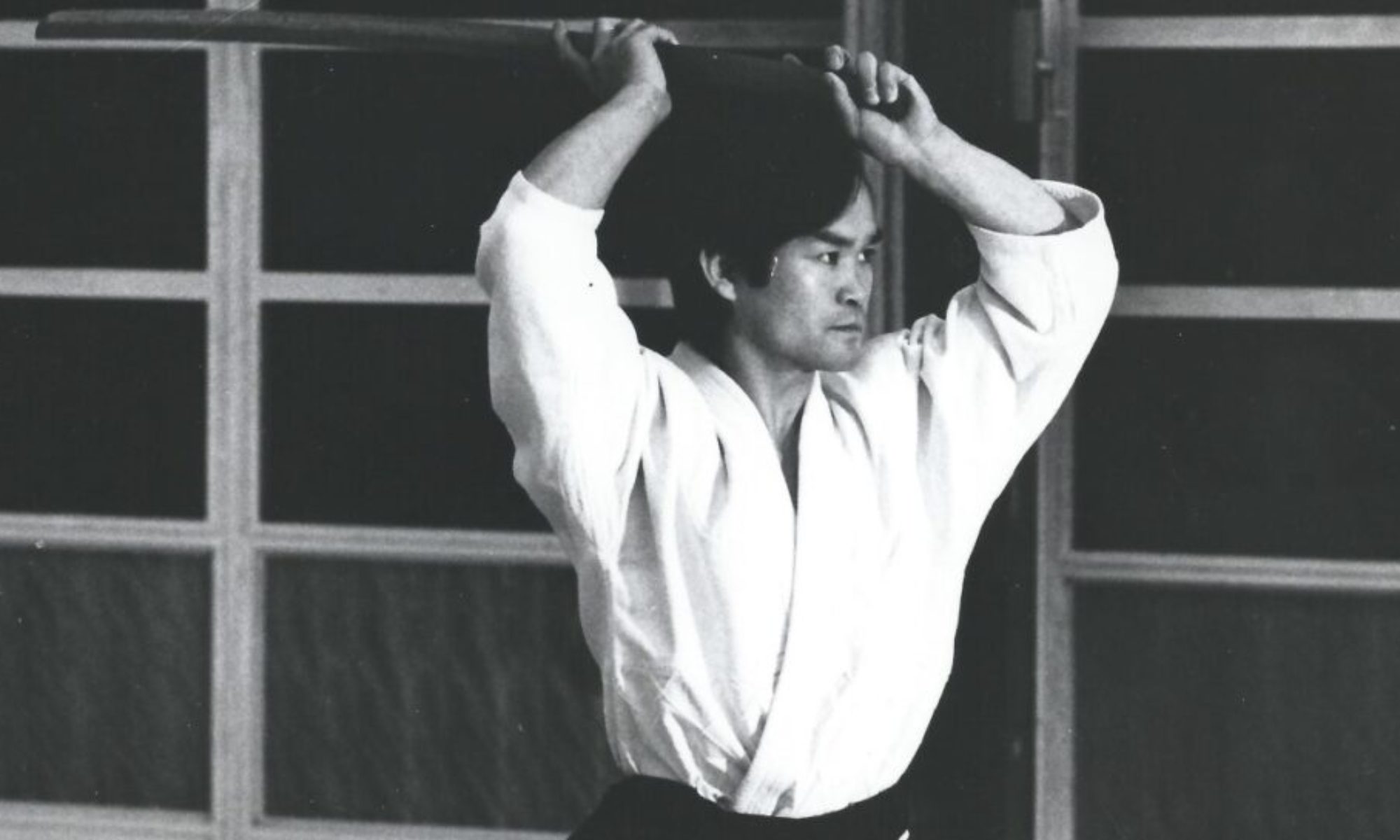

Grahame Vittorini, East Lake Aikido

表 (omote) – surface, face (of an object), public

裏 (ura) – side hidden from view, back (of an object), in the shadows

It’s very hard to be a white belt at a seminar. As the teacher finishes demonstrating and the students look for partners, a multitude of reckonings occur. People look around and might think, “oh, I know that person and they’d be good to work with,” or, “that person looks kind and relaxed and would go at a slow pace.” Or they might think, “wow, I should go work with Sensei’s uke,” or “they’re a white belt so they’ll need help with this technique.” These are all based on surface observations, though perhaps informed by previous experience or prejudice; I know this person or I know they’re a white belt.

If you’re a white belt, you might work with a senpai who treats you like a child or novice, or feel they need to explain things to you. They might even stop you from attempting to do the technique because it’s “wrong” or to provide a mini-lesson. They see one or two traits; outward indicators of accomplishment, background, culture, experience, etc. and choose this path. For the true neophyte, this might be comforting or appear caring; but for the more experienced it can feel condescending and frustrating. Especially as an advanced white belt, these experiences are frequent.

Despite being on the cusp of a modicum of understanding, that nikyu or ikkyu might be treated as something base and unmolded. Sometimes, this treatment comes from a place of negligence, superiority, and carelessness; almost an obtuse and intentional inattention from our partner. They didn’t attempt to join as an equal and through sincere and concerted effort grow with you, each technique elevating you both a little more and a little more and a little more…

The crassness is omote but instead we should strive for the ura. What shouldn’t I do? How shouldn’t I treat my kohai or strangers? How can I get the hell out of our way and just do the work? What can I wrest from this experience… this opportunity? How can I look at someone from afar and see how they hold themselves, how they move? How can I feel it when they touch me, connecting and engaging? Are they centered, connected, whole, lively, and open? These are all ura.

The omote can provide us with structure, explicit instructions, safety, and an anchor; but the actual art and its transmission is ura.

Doing what you’re told is omote; cultivating a commitment and respect for the dojo (a community of people) and doing what is needed is ura.

Prescribing the technique is omote;

feeling it through ukemi is ura.

The atemi is omote;

The waza is ura.

We should always be trying to snatch the ura: with our eyes during demonstrations, through our touch during techniques, from the sighs and exhalations of our partners and ourselves.

But some things must be explicit.

Consent must be omote.

Expectations must be omote.

Safety must be omote.

I reflect on these things and know that we cannot have the ura without the omote. There must be a front to have a back, there must be an outside to tear away or carefully dissect to find the inside. Sometimes omote is stifling, heavy, and unwanted; sometimes it is the ladder that leads us further up. Sometimes ura is a revelation, refreshing and unexpected; sometimes it is a sheer cliff face on a moonless night. We must hold this tension, cutting and polishing away the unneeded parts.