By Roo Heins and Cecilia Ramos

Cecilia Ramos:

Last year as I was driving to camp, I felt a disconnection from our group. The pandemic had brought a separation from the togetherness all of us had long enjoyed. I found myself wondering if there was still a way that I could contribute or if it was time for me to withdraw into retirement.

Camp was going to be held in Camarillo, California at California State University Channel Islands. It was a long eight-hour drive there from my home in the mountains of Northern California. As I drove, I remembered that the university had formerly been the site of a mental hospital for the criminally insane. It was also rumored that it was the inspiration for the Eagles’ song Hotel California, one of the great rock songs of all times. As I drove, the melody of the song got stuck in my head, along with its famous line, “You can check out anytime you like, but you can never leave.” It seemed to mean something for us in Aikido, we can never really leave… (although we do have steely knives and we can kill the beast within…) We are not criminals, but we might be considered insane!

As I drove through the Tehachapi Mountains toward camp the thought popped into my head that perhaps a way I could help Birankai might be to revive Biran Online. Once I got to camp all my odd fears of irrelevance faded away as I reconnected with old friends and made new friends. I floated the idea by various people of kick-starting Biran Online as a “voice of the people” and received encouragement at every turn. So I took it on and made the first post in September. Since then, we have posted twice a month without fail.

At a Teachers’ Council Meeting, John Brinsley Sensei announced that the 2025 camp would be held in memory of the ten-year anniversary of Chiba Sensei’s passing. He suggested we collect stories of Sensei to make into a little book. I quickly put out a call for stories. Many have already been posted on Biran Online. Brinsley, Savoca, and Heins Senseis came together and between us we recruited some of Sensei’s direct students to write their stories for the book. These stories have not yet been posted to Biran Online, but the book (a chapbook, a literary term I had to look up) will come out at this year’s camp!

Roo Heins:

I’m pretty sure it was Ryūgan’s idea. Somewhere in January he said to John Brinsley and me, “I feel like we need to honor Sensei properly on this anniversary. And there are a lot of people with stories about him, and I don’t want them to get lost. This is our chance to commemorate him properly.” Having some professional experience with creating books, I tried to impress on him what a major undertaking this would be. “It could be a nightmare. Chasing people down for writing. Probably if you ask fifty people, only twenty will actually come through. Then we have to edit everything. And find photos. And then lay it out for publishing, and proofread it. Then find somewhere to print it. How will we pull that off?”

But Ryūgan also has experience with making books, because Brooklyn Aikikai puts out a regular journal along similar lines—a softcover volume of writing and art organized around a theme, contributed by dojo members and associates. This wouldn’t be too different from the journal, he insisted. Somehow he convinced me to be responsible for copyediting and layout, provided that I could get help from Sean, the amazing designer who does the Brooklyn journal. John and Cecilia agreed to help with soliciting articles and editing.

We started by making a list of people who might contribute a piece about Sensei. We decided to limit it mainly to people who had studied directly with Chiba Sensei in San Diego or who had worked with him over a long period of time. We kept our list to North America, reasoning that Birankai groups in Europe and elsewhere might want to make their own memorial publications. We included Didier Boyer and Mike Flynn, however, because they both were going to be teaching at Summer Camp this year. We split up all the names among the four of us, so we each had a group of people to correspond with about writing. Looking back, I wish we had cast a wider net—asked more people who trained back in the day but aren’t involved in Birankai anymore, perhaps—but we were pressed for time. I made a rough schedule and calculated that I had to finish layout by May 15 in order to be sure the book would be done in time for Camp. I had never laid out a book before—though I’ve edited many both before and after layout—so I wasn’t sure how long it would take. I wanted to have a good four weeks for editing and at least four weeks for layout, so that meant we had to have everyone’s writing in hand by the end of February.

To keep everything in “real time” and avoid sending files back and forth, I decided we would use Google Docs for copyediting. This didn’t work out well in practice, since editing that way has a rather steep learning curve and not everyone had experience in it. It’s also just a clunky program. I ended up importing edited files into Word so I could track the edits, and this added a lot of time to the process. To complicate matters, I have two different email addresses, and while I tried to keep the project contained to my gmail address, people inevitably sent messages and files to my old yahoo address. This made it even harder to keep track of things. There was one essay that got overlooked until I was finishing the layout. I had to hastily edit it and sneak it in at the last minute!

For the editing, we basically used Chicago style, but I made the editorial decision not to italicize many commonly used Japanese words, like kenshusei and ukemi. I also tried to restrict the edits to revisions for grammatical correctness or clarity, without changing the writer’s voice or presentation. In a few cases I had to cut text because it was repetitive or detracted from the focus of the essay. I also had to fact-check details in some cases—memories are tricky things. In one case I had to ask for the piece to be rewritten, as it crossed some privacy boundaries. But for the most part the essays were all excellent and quite straightforward to edit.

What I didn’t expect was how reading all the pieces would affect me emotionally. I left San Diego in 2004, and while I remained in close contact with Sensei until a few years before his death, I closed off most of my memories of training with him. As I read what others had written about their experiences with him, my own recollections began to stir. It was bittersweet and painful. I didn’t realize how deeply I missed him.

April arrived, and I had to start laying out the book in InDesign. I had used the program for editing text, but I had no idea how to work with images or flow text onto the pages. Sean was my savior—he patiently guided me through the process of inserting each essay (and kindly allowed me to use the Brooklyn journal as a template) and talked me down from my tree on Zoom when I emailed him in a panic because couldn’t figure out how to fix some mistake or other.

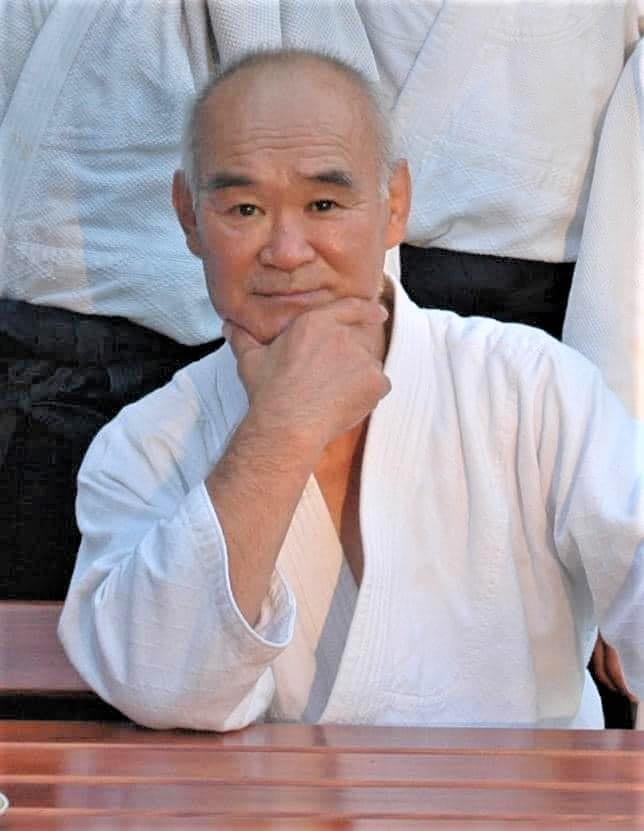

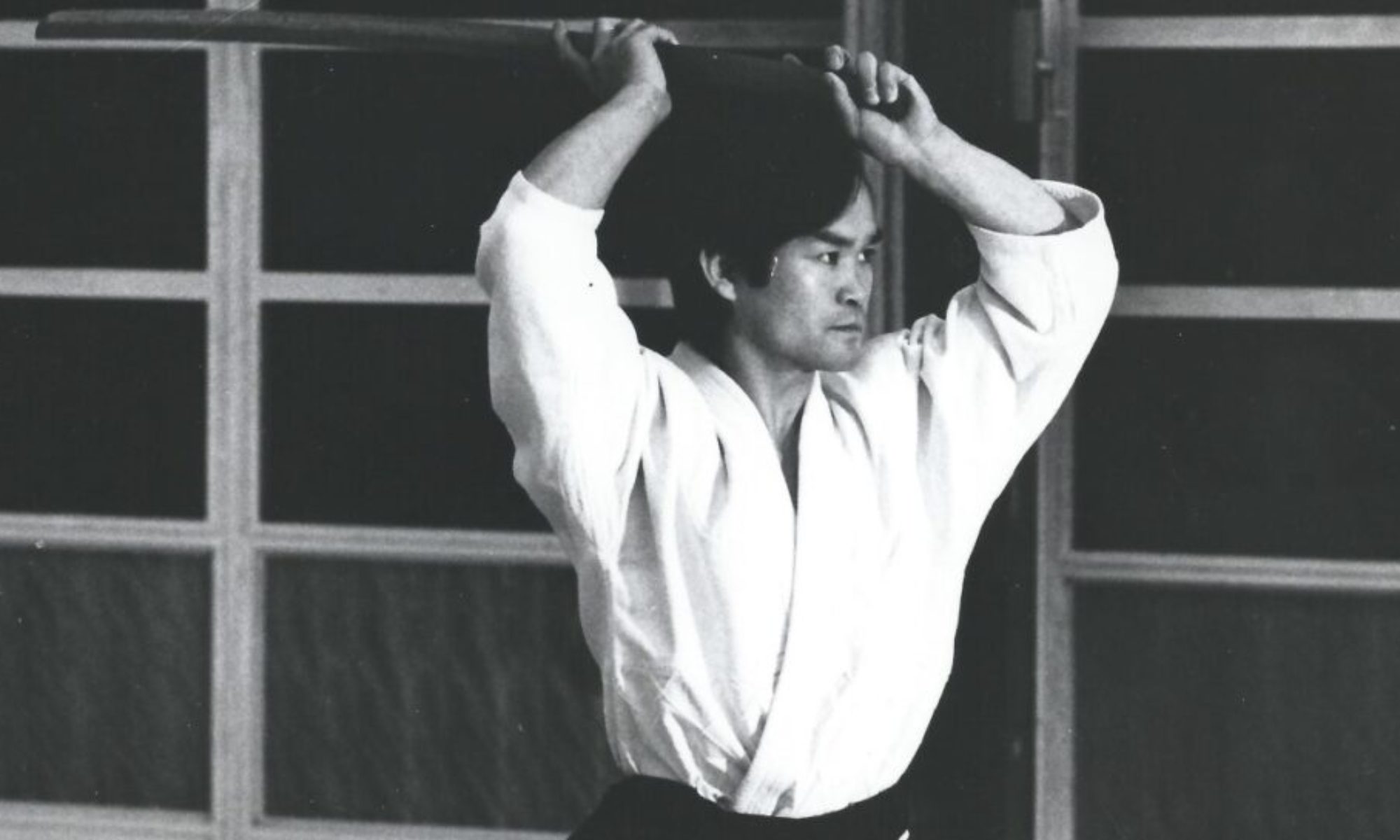

As I put the book together, I realized I needed more photos. I had a folder of pictures of Chiba Sensei, but the quality was inconsistent. I needed high-resolution professional photos. Luckily, Ben Pincus contributed a bunch taken by photographer Scott Brightwell when Sensei was teaching in Vermont. And Gary Payne came through with a gold mine of images taken from Summer Camps across the years. Those two sources, supplemented with photos from various other photographers (many collected by Diane Deskin), gave me gorgeous images to bring the essays to life. It’s wonderful to have this kind of documentation of Sensei as he taught and observed practice.

I finished laying everything out around May 20. Every time I read through the book, which was now more than ninety pages long, I found a new typo or error to fix. Generally speaking, it’s best practice to have the copyeditor and the proofreader be two separate people. Once you’ve gone through a book as a copyeditor, your eye is no longer fresh, and you are likely to miss errors. So I asked a couple folks to help me review it, and I sent each writer the pages with their article so they could make sure everything looked OK. This caught a few more mistakes, including a couple major ones (one essay’s title had somehow been changed so it meant something completely different than what it was supposed to mean—yikes!). Several of the photos had to be cleaned up, which Sean helped with. I had to create the cover, with help from Ryūgan and Sean. This was when I learned the Rules of Design, which are as follows:

- Have good taste.

- Don’t have bad taste.

(I’m still working on mastering these guidelines.)

Then, just as I was about to send the final PDF to the printer, John said that Doshu had written an introductory note for the book! I had to add a new spread with Doshu’s letter in Japanese and John’s translation on the facing page. It felt really wonderful to be able to include this tribute, even if it added a bit of pressure to the deadline.

There were a couple more hiccups, but somehow I finally got the thing wrapped up and sent to the printer in time. The book has now been printed and is in transit to Burbank as I write! I hope it touches those who read it; that it stirs up fond memories of Chiba Sensei in those who knew him and gives those who didn’t a sense of what he was like. It was a privilege to have been involved in making this tribute to the memory of our teacher.

Editor’s note: All resident participants at this year’s Summer Camp will receive a complimentary chapbook honoring the 10th anniversary of Chiba Sensei’s passing. Those not attending camp or commuting to camp may pre-order a book by completing this Google Form. The chapbook is available for just $20. You may pick up your order at camp or have it mailed to you (additional mailing charges will apply). A limited number of copies will be available for purchase at camp but pre-ordering is best to guarantee your copy. Payment options are cash, check, Venmo (@Bianca-Zeinali), or Zelle (BNAEventCoordinator@gmail.com).

Wow!!! That’s pretty much all I’ve got- wow !!!