Darrell Bluhm, Founder and Chief Instructor, Siskiyou Aikikai and Cultivating Connectedness Webinar Moderator

Much of the credit for the conception, organization and presentation of the two webinars must go to Rob Schenk, Chief Instructor of Aikido Institute of San Francisco, and technology wizard. Rob initially proposed the idea of Birankai North America holding webinars and offered his expertise to the organization to make them happen, serving as host to both events.

Personally I’m grateful to Rob for prompting and supporting us in creating a means to remember and honor Chiba Sensei with the first “memorial” webinar on June 6th. I felt strongly it was important that we, as a community, could come together during this challenging time in remembrance of our teacher.

While I was involved in planning that event, I participated as an audience member and greatly enjoyed hearing the stories and comments of my colleagues and friends. For me it was a healing balm to the feelings of sadness and emptiness that still arise within me as I continue to miss Sensei’s physical presence in my life. I was also encouraged by the level of participation and general enthusiasm expressed during and after the event.

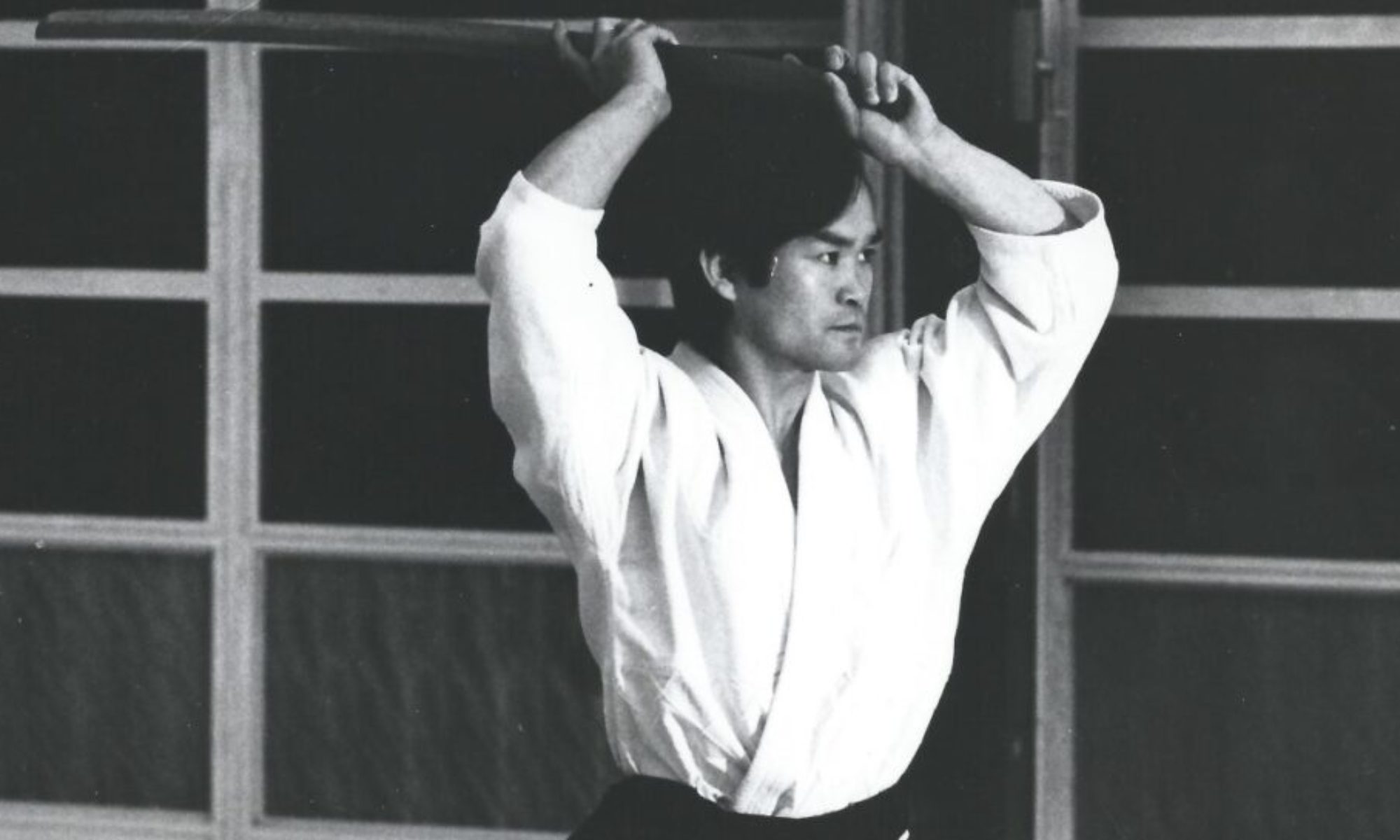

The success of the memorial webinar led to a desire to host a follow up event, in part, to create an opportunity to address some of the questions that remained unanswered from the first webinar. We chose to focus the discussion on Chiba Sensei’s development of bokken and jo practices and their integration into the whole of his Aikido “curriculum”. This choice was stimulated by the reality that for many of us, our weapons practice is what sustains us during this time of social distancing where the physical contact we’re accustomed to is not readily available.

The selection of panel members was made with the intention to select teachers with extensive weapons training and experience working directly with Chiba Sensei. The panel clearly met that criteria and were able to provide a lively and entertaining conversation. This time I did have the opportunity to participate actively in the event as the “moderator”, a role that proved much more enjoyable than I imagined!

It’s my hope that we will continue to hold these kinds of webinars going forward, with a wider level of participation and structured to address the needs and interests of our teachers and general members.