Introduction

Oh, mirror in the sky

What is love?

Can the child within my heart rise above?

Can I sail through the changin’ ocean tides?

Can I handle the seasons of my life?

Well, I’ve been afraid of changin’

‘Cause I’ve built my life around you

But time makes you bolder

Even children get older

And I’m getting older too

“Landslide”, Stevie Nicks

At this year’s summer camp I prefaced my class by saying it would probably be my last summer camp class. This year was my 40th camp and as the song goes, “I’m getting older too”. Part of getting older involves reprioritizing our time and time with family has to be my priority going forward.

At the conclusion of the class I read from an article I wrote 30 years ago titled “Mature Body, Mature Character” that includes a poem by Wendell Berry, titled “Ripening” that several people asked me about afterwards. Cecilia Ramos has agreed to republish the complete article in Biran Online and I would like to give a little context regarding the original writing of it and why I find it relevant now.

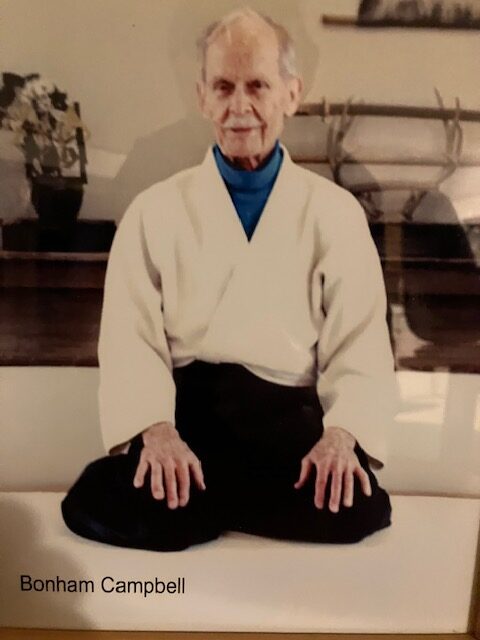

The topic for the article was assigned by Chiba Sensei and it was, at the time, one that resonated with me. I was 45 when I wrote the article and I had a number of students that were 10 to 30 years older than myself. Much of what is written was inspired by them, in particular, my student/mentor Bonham Campbell, who began training with me when he was 73. He continued to train until he was 90 when he said to me, “Sensei, it’s time for me to step away from my “little practice”of aikido on the mat, but I will continue to practice my “big aikido”, which he did for the remaining two years of his life. At the time I wrote the article Bonham was over 80 and training vigorously. As I grow older, now having circled around the sun 75 times, I realize how remarkable Bonham was and my gratitude for his presence in my life grows daily. Truth be told, Bonham’s technical development as an aikidoka was never his strength but his grasp of aikido as a spiritual practice rooted in physical training and his ability to live the ethical principles of aikido were exemplary. By accepting me as his teacher Bonham taught me more about what the student-teacher relationship can be than anyone, with the possible exception of what I learned through my relationship with Chiba Sensei. Bonham was clearly an “old dog” capable of learning “new tricks”, having maintained an unquenchable curiosity rooted in an attitude of beginner’s mind (shoshin) through the entirety of his life.

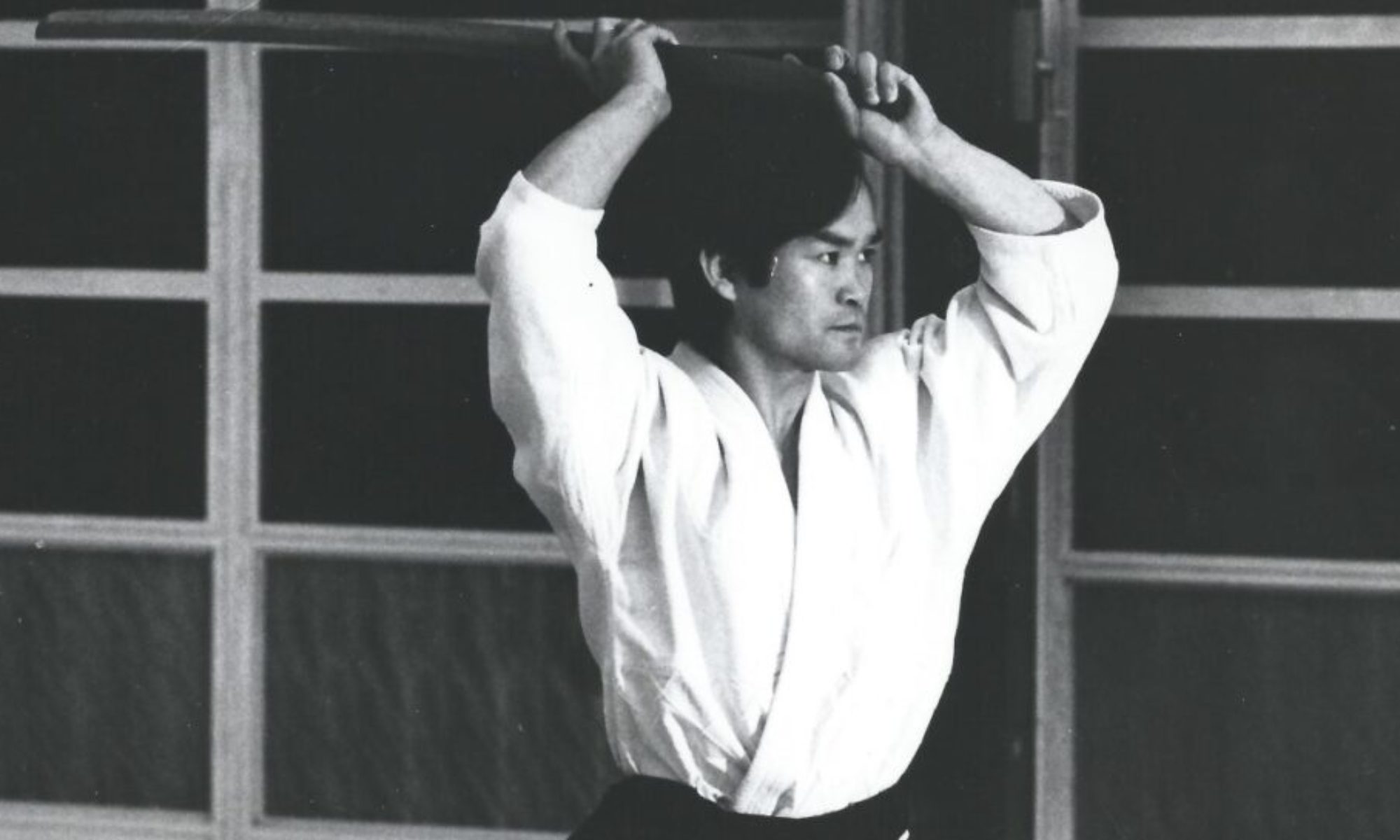

At this year’s summer camp’s panel discussion held in remembrance of Chiba Sensei someone asked if Sensei taught much about teaching aikido to those of us he brought up as teachers and it was a question I thought that did not get well answered at that time. One comment I would make regarding that question is that Sensei told me on several occasions that the single most important thing I could “steal” from him was the process he developed for helping his students forge their “Aikido Body”, which he at times also referred to as their “natural” or “mature” bodies. This article was possibly the first of several articles I have written over the past 30 years on the primacy of developing the body and perception through training.

Darrell Bluhm

Mature Body, Mature Character

Darrell Bluhm, Siskiyou Aikikai

“The human soul itself is quite ordinary, existing by the billion, and on a crowded street you pass souls a thousand times a minute. And yet within the soul is a graceful shining song more wonderful that the stunning cathedrals that stand over the countryside unique and alone. The simple songs are best. They last into time as inviolably as the light.”

Mark Helprin, Memoir from Antproof Case

The term mature body as I understand it does not refer to the aged body, but refers to a possible physical development of an individual that is realized through having lived a requisite number of years (five or more decades) and having cultivated an intelligent use of one’s self. The mature body then emerges as the consequence of developmental processes (birth to infancy to childhood to adolescence to adulthood to maturity to death) coupled with learning drawn from a vital connection to one’s bodily experience.

Qualities I attribute to the mature body are grace, ease and economy of movement, a center closely aligned with the earth and vitality of expression (a richness of voice and gesture). The mature body expresses power more from presence, efficiency and timing than strength, effort and speed. The mature body exists only in union with a maturity of character and gives outward expression to the “graceful shining song” of a unique soul. Individuals I think of as examples of this maturity of body are Marcel Marceau, Martha Graham, Dizzy Gillespie, and of course 0-Sensei. (I have been told that O-Sensei felt he reached his physical peak as a martial artist in his mid-sixties.)

To mature in our time requires one to act in opposition to dominant forces within our culture. Traditional wisdom has taught that humanity exists as part of the world not apart from the world, yet modern man has set himself in isolation from the world and arrogantly imagines to have dominion over Nature. This arrogant misperception of our place in the world is central to the ecological disaster that has been wrought by our civilization. In separating ourselves from the natural world we separate ourselves from ourselves (our bodies from our souls – our souls from the soul of the world). The relationship of destruction we as a culture have with the earth is reflected in a relationship of alienation with our body.

As the poet Wendell Berry writes in his book, The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture: “You cannot devalue the body and value the soul – or value anything else… Contempt for the body is invariably manifested in contempt for other bodies – the bodies of slaves, laborers, women, animals, the earth itself… The world is seen and dealt with, not as an ecological community, but as a stock exchange… The body is degraded and saddened by being set in conflict against the Creation itself, of which all bodies are members… The body is thus sent to war against itself. What this conflict has done, among other things, is to make it extremely difficult to set a proper value on the life of the body in this world – to believe that it is good, be it short and imperfect. Until we are able to say this and know what we mean by it, we will not be able to live our lives in the estate of grief and joy, but repeatedly will be cast in violent swings between pride and despair.”

To ripen into a mature relationship with our bodies and the world, we have to embrace the traditional wisdom that places us in the midst of an interdependent web of life. The mature body is nourished through its relationship with the community of bodies.

Aikido practice offers us a powerful means by which each of us can come into a relationship with ourselves that makes no room for contempt toward our body but creates an open sky for wonder. Chiba Sensei once compared the relationship that we develop with our body through training to the relationship we establish with a lover. To come into and sustain a loving relationship with our body means we have to overcome tremendous cultural conditioning that denigrates, objectifies and romanticizes the body. In entering into this personal marriage of the self to the body we are able to come into dynamic contact with others and the world. Love of any kind demands discipline, commitment, the acceptance of imperfection and giving up of egocentrism. When we love and live within “the estate of grief and joy” an adequate length of life, we can ripen into our mature selves (body/character).

Again Wendell Berry from his poem:

Ripening

We, who were young and loved each other ignorantly, now come to know

each other in love, married

by what we have done, as much

as by what we intend. Our hair

turns white with our ripening

as though to fly away in some

coming wind, bearing the seed

of what we know. It was bitter to learn

that we come to death as we come

to love, bitter to face

the just and solving welcome

that death prepares. But that is bitter

only to the ignorant, who pray

it will not happen. Having come

the bitter way to better prayer, we have

the sweetness of ripening. How sweet to know you by the signs of this world!

I have been blessed with a core of senior members in my dojo who have come to their aikido practice having lived long, knowing much grief and joy. They use aikido to further develop and give focused expression to their mature body/self. Beginning the practice of aikido late in one’s life presents many challenges but these older students bring the strength of character and an understanding born of experience that provides them the means to meet the challenges with a tenacity, self awareness and humor that younger students lack.

Of the challenges that the older student faces two stand out. One is the real physical limitations they bring to their practice due to injury, illness or acquired habits of posture and movement that younger students lack or do not have as deeply entrenched. Secondly, the older student has to overcome cultural stereotypes and attitudes about aging.

The forging of the body that we undertake in order to embody aikido is challenging at any stage of life. We cannot assume that years of training will by itself be adequate to meet that challenge. If our practice becomes mechanical or habituated our capacity to give aikido expression will diminish with time rather than grow. Younger students often lack the discipline of attention and observation necessary to keep their practice sharp. It is a challenge as teachers to open their eyes outward and inward and focus their attention.

Older students usually have more discipline and focus but have developed fixed habits of movement that not only affect the quality of their movement but their ability to sense their movement. The gap that exists between what we want to do or think we do and what we in fact do can be immense, especially when the ability to feel our movement is diminished. Habits by definition are outside of our awareness or control.

Young students must be careful not to cultivate rigid or ineffectual habits of movement through unfocused practice, while older students must recognize habits that have developed over a lifetime of moving and sensing and learn new ways of feeling and acting.

In this culture we are taught that the advance of age to brings a decline in our capacity to learn, i.e. “old dogs can’t learn new tricks.” This attitude is quickly dispelled when we have the opportunity to have as students elders who have ignored or rejected such stupidity. Our capacity to learn only diminishes if our curiosity diminishes. Our elders who hold wonder alive in their lives teach us that learning is the natural consequence of engaged living. How we learn as we age changes as our bodies change. I cannot articulate what those changes are, but I recognize that they exist. My older students have taught me to respect their ability to learn and challenge me to challenge them.

To close this discourse on the mature body I want to be clear that I do not believe that the mature body is some ideal body. The mature body is a lived body which means it bears the effects of illness, injury and the wear born of work and play.

The processes of becoming ill and recovering and suffering bodily damage and learning to adapt may be necessary experiences to developing the mature body. The mature body can be expressed through damage, deformity or infirmity of flesh, it cannot however exist alienated from a whole person living within a given social and physical environment in a given time.

Reprinted from Sansho, Vol. 12, No. 3, Fall 1995

Darrell Bluhm, Jason Bluhm, and Cindy Eggers

I remember Bonham Campbell very well. He was the first person whom I wished I could be like. Don’t remember his age when we first started training but he never quit or asked me to slow down for him.

Such an incredible article. And always timely. I hope you will come visit our dojo and share even more.

Thank you Sensei Bluhm.