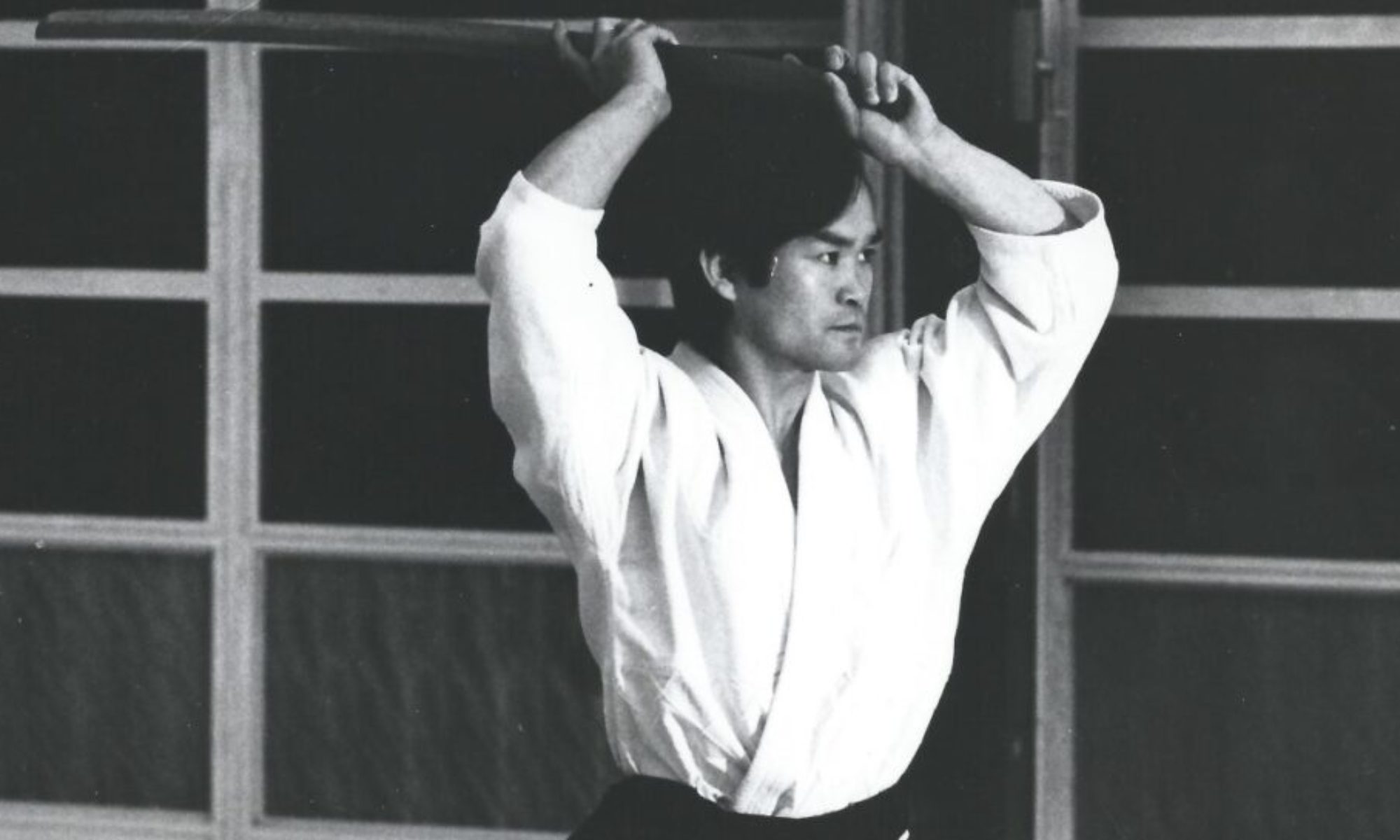

Darrell Bluhm, Founder and Chief Instructor, Siskiyou Aikikai

“Study your own body through basic forms. Study the centralization of the body.” – T.K. Chiba

Chiba Sensei often spoke of wanting those of us he trained as teachers to understand the ways he helped his students condition their bodies through and for training in Aikido. He expected us to be able to assist each of our students to develop what he called, “their Aikido Body”. When he spoke of the Aikido Body, he spoke not in the abstract but from his extraordinary experience in working with his own body, and from the practical means for shaping and conditioning his students’ bodies that he developed over decades of teaching Aikido to many different students in many different cultures. He would sometimes refer to the ‘Aikido Body” as the “Natural Body” or the “Instinctual Body.” However, he was very aware of how unnatural the social and physical environment of the modern world is. We humans have created a world for ourselves that resembles a zoo more than it does the wild world our hunter-gatherer ancestors lived in, and in which our bodies evolved. In a very real way, we resemble captive or domesticated creatures more than adaptive embodied beings. The question Chiba Sensei sought to answer for himself and for us is: How do we, as modern humans, reclaim the natural abilities that exist within each of us?

In trying to answer that question for myself, in this three-part series I look to the five principles of embodied Aikido which Chiba Sensei identified: centeredness, connectedness, wholeness, liveliness and openness. Underlying these principles is a foundational assumption that the body is inseparable from the mind, and (as stated in his essay “On Food and Diet”) the body and the Earth are one. While I will explore this topic from the perspective of the primacy of the body, I too believe the body exists in union with mind and no body/mind union exists independent of a social and physical environment.

Centeredness

We are literally shaped by our everyday movement. Much of our movement is determined by what is known as the “field of promoted action”: the ways we eat, speak, defecate, dance, and so on, in the culture we are born into. This is different from culture to culture and even family to family. In the Japanese culture of the early to mid-20th century when, through the genius of Ueshiba O Sensei, Aikido emerged, there was little need to teach people how to move from their center. This teaching was embedded in patterns of action woven into daily routines: sitting on the floor in various postures, moving from sitting or squatting to standing and back to the ground. Now, in the 21st century, sitting cross-legged or on one’s heels on the floor (seiza) is uncommon. The chair intervenes between bodies and ground for many contemporary people as soon as they learn to walk. We sit, often while looking at a screen, more than we engage in any other posture. This creates challenges, even when confronted with simple actions such as kneeling, bowing, or getting up and down with ease.

To understand what it means to be centered, and to know how to move from our center, we need to have a clear image of where our center is and how it is related to the whole of ourselves. Chiba Sensei taught a very simple action for us to use to sense where our tanden resides and how to engage it actively:

He had us lie on our backs, place our hands by our sides (or sometimes place our fingertips on our lower belly) and with a sharp inhalation lift our head, arms and legs from the mat, hold for a moment and then with our exhale release our head and legs back to the mat. Try this for yourself. You will feel the engagement of your tanden and hopefully experience a sense of physical unity. This should be done carefully and without excessive muscular effort. Locating the center is the first step in cultivating our ability to use our centers dynamically.

To move in any way, we have to coordinate the mobilization of some parts of ourselves while stabilizing others. Given that our physical center resides in the basin of our pelvis, to mobilize that center requires fluency in the movement of the hip joints. If you watch video of Chiba Sensei conducting warm ups, you will see many actions both in standing and seiza that require movement in all planes of action, where the pelvis rotates over the hip joints, or the hip joints move relative to a stable pelvis, as well as very dynamic use of the tanden and breath:

For kinetic energy to be transmitted from the ground through the body to the hands, the hip joints must be fluid and the spine must be well organized, extended, flexible and stable. As teachers working at this time, we need to recognize that a life of accommodation to the chair has compromised the ability of most individuals entering our dojos to move freely at the hip joints or to have the requisite flexibility in their feet, ankles, and knees or the stability in their spines to execute the most basic actions of our art, sitting, bowing, suwariwaza, etc. Chiba Sensei modeled many ways to address this reality both through his warm ups and conditioning exercises, and in the precision with which he executed basic Aikido forms. I believe that going forward we need to study what he developed, and to expand it to meet the needs of our present students.

“Everything is hidden within your spine. The state of the spine is an indicator of the unification of the body and spirit. To study the body is to study your spine.” – T.K. Chiba

The primary function of our skeleton is to provide support to the body within the field of gravity. As upright, bi-pedal creatures with large brains — and consequently heavy heads — that task is complex. Literally central to that task is our spine. As mentioned earlier, in order for us to move freely, the spine provides the stability to transmit the forces generated by gravity downward and the forces generated by ground reaction forces and muscular action upward. Skeletal alignment, the organization of parts to each other and the whole relative to the ground, develops for us during infancy and early childhood. The movements of rolling side to side, front to back, lead to sitting and crawling, and create the strength and organization of muscles, connective tissues and proper neurological stimulation necessary to then stand, walk, run, jump, roll, etc. Returning to a closer relationship to the ground through seiza, shikko, rolling, etc. gives us an opportunity to refine and expand the quality of our movement by strengthening the stability of the pelvis and spine and their ability to support the actions of the body as a whole.

The quality of support we sense, relative to the ground, influences the amount of effort and the distribution of effort utilized in any action. Just as learning to walk as children required moving from the ground up, learning to move from our center in Aikido is promoted by the practice of sitting in seiza and executing suwariwaza (kneeling) technique. Paradoxically, our instability as upright creatures enhances our overall mobility. All martial arts involve an exploration of stillness and motion. Finding stillness in standing is required in balance poses in yoga, the most basic being Mountain Pose or “Tadassana.” Tadassana is very challenging, yet, moving from standing requires almost no effort. I have become very aware, in my personal Iai-batto ho practice, of the difference between moving from the large triangular base provided by sitting in seiza compared to moving from standing, At this point in my life, due to 70 years of wear and tear on my knees, seiza and shikko are no longer accessible to me. The foundational form in our system of Iai is Shohatto, executed from seiza. The standing version of Shohatto is called Koranto. This form has become the root of my present practice. Without the years of practicing Shohatto and its sibling forms, from sitting, where stillness is more readily available and moving from an engaged and vital center is essential, I would not be able find the rhythms of stillness and motion, mobility and stability, necessary to execute Koranto in a satisfying way.

If we as teachers of Aikido within Birankai wish, as our newly drafted vision statement states, to “meet our students where they are”, we need to develop ways to help them find comfort in their relationship to the ground and learn to mine the treasures accessible to them in the fundamental actions of sitting, bowing, knee walking etc. For those who can’t get all the way to the ground, we may need to explore ways we can help them discover their centers and how to move dynamically from their centers in and out from a chair (or zafu). What we must never do is remove seiza, bowing, shikko, etc. to accommodate the many who will be challenged by them. To do that would be to abandon the foundations of our practice.