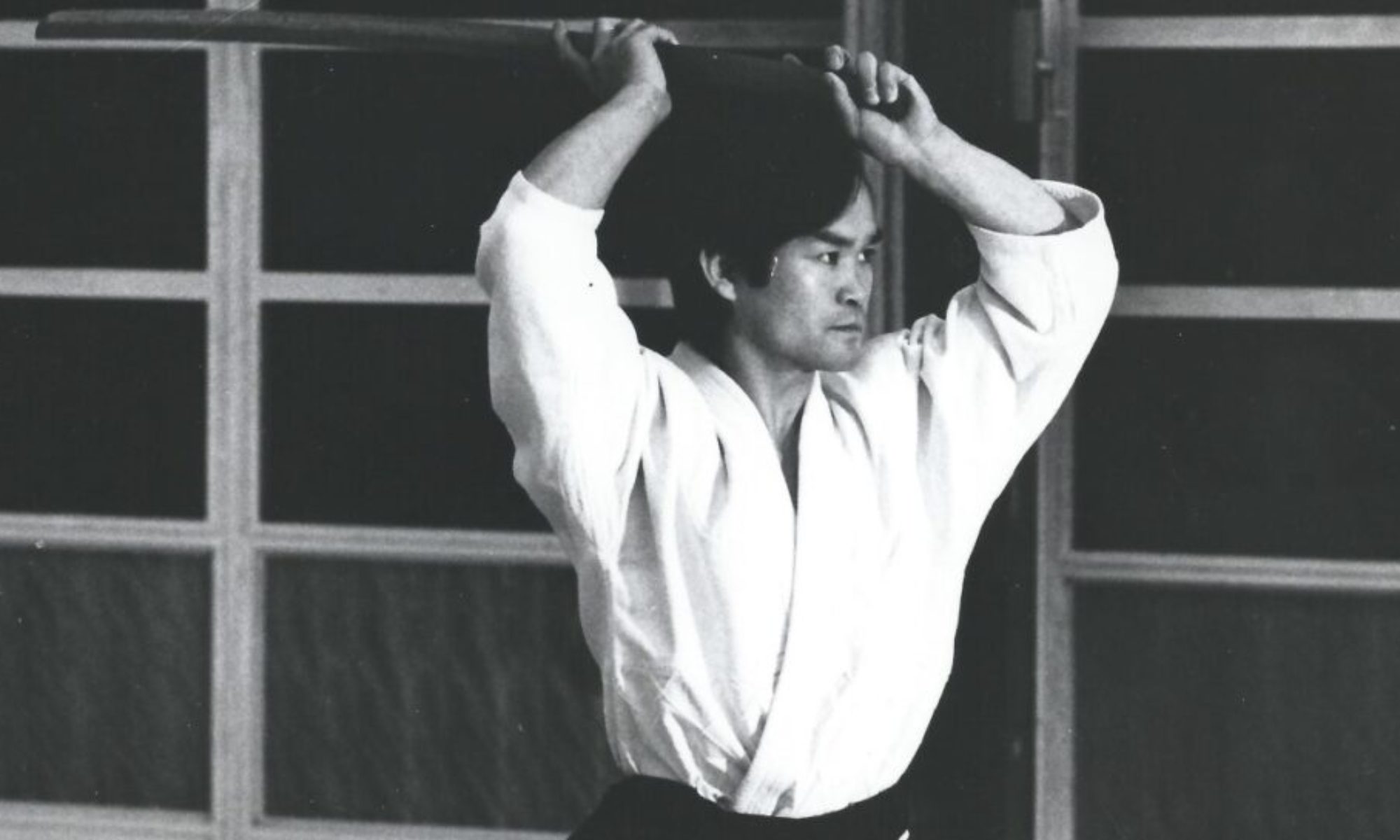

T.K. Chiba Shihan, Birankai Founder

The article “Structure of Shu, Ha, Ri, and Penetration of Shoshin” was first published in the 1989 Winter edition of Sansho, the Aikido Journal of the USAF Western Region. Two more articles on Shu-Ha-Ri followed, which were transcribed from interviews between Chiba Sensei and Shibata Sensei.

The article below was written when Sensei was a fully mature teacher with a clearly developed methodology to his teaching. Having taught Aikido for nearly 30 years, Sensei presented his understanding of “shoshin”, beginners mind, in a clear and powerful way. In his last advice to us, his students, in 2015 he returned to this frequently referenced principle, admonishing us to never lose our beginners mind.

Sensei’s later essays on Shu-Ha-Ri expanded upon the concepts below, striving to help students assess their current and future levels of development. He wrote, “I am writing about Shu-Ha-Ri to help students understand where they are in terms of the stages of advancement in training. By developing ‘eyes to see’ what stage they are in, I want them to grasp what direction to take in their future training.”

This article and the principles presented in it introduced elements of Sensei’s teaching that he continued to develop through his life. They are central to what he gave us. Please read with an open heart and an open mind.

–Darrell Bluhm Shihan, Ashland, Oregon, 2 January 2020

Among those words we commonly use and supposedly understand are those that, when paid close attention to in order to define their meaning, reveal how unclear and obscure our understanding really is.

Perhaps the word shoshin, which is commonly used by martial artists, is one of these. It is understood that Budo (martial art) begins with shoshin and ends with shoshin. Budo, therefore, cannot be understood without first having a clear definition of the meaning of shoshin.

What follows is a description of the meaning of the two Chinese characters that make up the Japanese word shoshin: The character sho means first or beginning. The character shin means mind, spirit or attitude. The two together have been translated as “beginner’s mind” and indicate the mind (spirit or attitude) of a complete beginner when starting Budo training. This is marked by modesty, meekness, sincerity, purity and a thirst to seek the path.

In Japan, Budo discipline is commonly recognized as, or expected to be, severe and hard, requiring many years to master. Within shoshin one finds a spirit of endurance, sacrifice, devotion and self-control. Why do the Japanese see Budo training in this way? (In contrast to the American attitude where, in general, it seems that pleasure and enjoyment come first.) The Japanese understand that it is impossible to master the art without the determination to go through many years of training, passing through various stages and being required to go to one’s physical limit and sometimes even beyond. The Japanese also recognize that in the final completion of the physical mastery of the art, there is spiritual realization that can take one further.

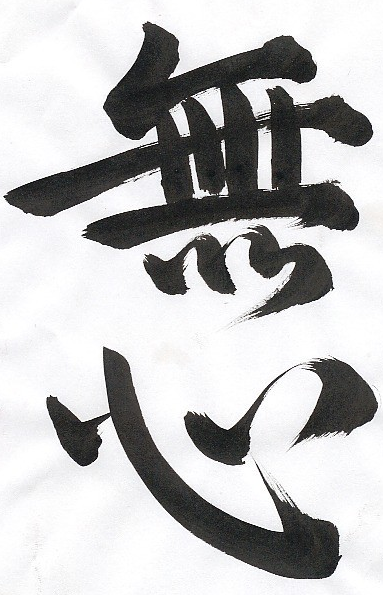

The state attained through spiritual realization, the highest state of Budo, is often expressed as mushin, the state of No-Mind. It is represented by the image of a clear mirror reflecting everything that comes before it exactly as it is. The state of No-Mind reflects everything that passes in front of it, whether coming or going, without interference of will or self-imposed view. However, there is an important distinction between a static mirror and this active state of mind. The active mind responds spontaneously and simultaneously to the reflected image without attachment or interference, right or wrong, gain or loss, life or death. What makes this state more difficult to attain is that it requires physical motion (technique) to simultaneously accompany the mind responding to the images reflected upon it.

The state of mind like a clear mirror — the state of No-Mind — may be attained through other spiritual disciplines such as meditation. What makes Budo unique, however, is found in the simultaneous and inseparable embodiment of mind and the physical motion (the technique.) This stage of training is known as the Sword of No-Mind or the Sword of No-Form, or even as the Sword in a Dream. Only when this stage is attained is one’s art considered complete.

Shoshin is the mind or attitude required to follow the teaching. This implies sincerity, modesty, meekness, openness, endurance, sacrifice, and self-control unaffected by self-will, judgment or discrimination. It’s like a piece of pure white silk before it is dyed. It’s also an important condition for the first stage, in which a beginner learns to embody the basics precisely, point by point, line by line, with an immovable faith in the teaching.

Shoshin, however, is not only the state of mind required for a beginner, but must be present throughout every stage of training. The manifestation of shoshin therefore varies depending on one’s status: whether a beginner, intermediate, or advanced student. What’s most important is that one becomes, ultimately, one body inside and out, finally developing into Mind of No-Mind. This is the completion of Budo training.

One’s determination to hold firmly onto beginner’s mind is a key factor in the completion of one’s study. But how difficult this is to do! That determination is very vulnerable to being destroyed by fame, position, rank, or being lost through haughtiness or conceit.

Like everything else, shoshin encounters and experiences various challenges and can retreat, weaken, decay, or break down. It also can become clearer and stronger.

It’s vital to maintain a strict, self-reflective attitude throughout study to prevent shoshin from decaying or breaking down. It is necessary to be decisive, crawling out from a crisis not just once, but twice, three times, to keep on going. Loss of shoshin means the stopping of growth, and this almost always happens where and when one does not recognize it. This is a characteristic of losing shoshin. It is both a sign and a result of human arrogance.

If arrogance is the main cause of losing shoshin, modesty, its counterpart, is necessary to maintain it. A modest mind is one that recognizes the profoundness of the Path, knows fear, knows the existence of something beyond one’s own reality, while continuing to grasp one’s internal development.

Shoshin is also an idea strongly associated with self-denial, while arrogance is founded upon uneducated self-affirmation and superficial self-assertion. In many senses, self-denial works like a mid-wife to stimulate the birth of a true richness of heart. Paradoxically, while self-denial broadens, the reflection and understanding of human nature deepens.

In general, the difference between Americans and the Japanese lies in whether hardship or pleasure/enjoyment are anticipated in the study of Budo. This seems to be largely due to differences between the two cultures.

There still remains a strong influence from medieval ideas within all Japanese traditional artistic disciplines, including Budo, as well as within the present day Japanese consciousness.

It is largely because of Yoshikawa’s work on Miyamoto Musashi that Musashi’s life is deeply appreciated by the Japanese people. He has now become a long-standing national hero. This is not only due to an appreciation of his accomplished swordsmanship, but also an appreciation of his austere way of life, which deeply moves Japanese consciousness. A similar respect can be found in the attitude of the Japanese people towards O’Sensei, the founder of Aikido. Despite the differences between Musashi and O’Sensei (the Zen influence strongly characterized Musashi’s life, while Shintoism influenced O’Sensei), what is common to these two gigantic individuals is the depth of their self-denial.

It is necessary to pay strong attention to the profoundness of this self-denial because it contributes to the birth of an even stronger self-affirmation.

Self-denial is a vital force that contributes paradoxically to the development of humankind. Through self-denial, one can attain cosmic consciousness and achieve greater self-recognition by transcending the restraints of the ego.

This process is basic to the progressive development/structure that is commonly understood within the traditional artistic disciplines, including Aikido. However, before I enter more deeply into this subject, I would like to touch briefly on the meaning of kata.

The Role of Ki in the Practice of Kata

The study and disciplines of kata are the fundamental and common methods found throughout the traditional Japanese arts, such as the tea ceremony, flower arranging, painting, calligraphy, dancing, theater and Budo.

Kata has been translated into English as “form.” However, “form” seems to cover only one part of a larger whole, superficially limited to the physical appearance of kata.

While form covers only the physical part of the whole (the visible part of kata), there is another element that works within, which is invisible in nature. It is the internal energy associated with the flow of consciousness (ki). There are schools to be found in the old records of budo which describe kata as the Law of Energy, or the Order of Energy. Kata, therefore, does not limit its meaning merely to its physical appearance. Its appearance can be taught and transmitted physically with reasonable effort, as it is visible. However, the internal part requires a totally different perspective and an ability to master it. Since it cannot be seen physically, it cannot be taught but must be sensed and felt.

Ki, for instance, as a manifestation of control and flow of consciousness, works jointly with physical energy inside and outside of the body within kata. It is sensitively associated with the quality and combination of opposite elements that integrate and exchange: purity and impurity; brightness and darkness; wholeness and emptiness; contraction and expansion; positiveness and passivity; hardness and softness; lightness and heaviness; explosiveness and quietude; speed and slowness, and the like.

Kata comes into being as an organic life form when the two opposing elements, inside and outside, harmoniously integrate within a martial necessity. The kata then breathes, manifests, comes into being, and dies at the moment of execution. One must then let it go.

Furthermore, what makes kata significant is that it is deeply characterized by a school, especially a school’s founder, as well as the school’s successive personalities and experiences. Ultimately it crystallizes as a particular philosophy, which is then passed down to its successors. This is the heart of the school.

In its original form, kata is described as combative motion (against an enemy) and is the accomplishment and collective essence of each school. It results from the pursuit of efficiency, economy, and rational thought in any given circumstance.

By being exposed to — and trained in — kata, under a methodology unique to a school (or teacher) for a number of years, one can learn the physical forms and internal order of energy as well as being penetrated by the heart of a particular school.

Although the foundation of Aikido training is based on the repetition of kata, its approach is much freer and more flexible than in the old schools. It can be said that it is kata beyond kata. The reason for this can be found first of all in the positive fact that Aikido draws a wide diversity of people to it, compared to other budo disciplines. However, on the negative side, this contributes to a superficial overflow of individualism.

The second reason can be found in the fact that the Founder himself repeatedly transformed and changed his art and in particular its physical presentation. These changes were synonymous with his personal development and age. Without doubt, this is one of the reasons we see the different styles of kata, or different ways of expressing the essence of the art, among his followers. These students completed their training under the Founder at different periods of his life.

This continual development of Aikido is clearly due to the Founder’s endless exploration of the Path, a search with which, I assume, he was never satisfied. The best way that I can describe his attitude in this regard is that he used to tell his followers that if they advanced fifty steps, he would advance one hundred. I’m convinced that it was truly his intention to encourage his younger followers.

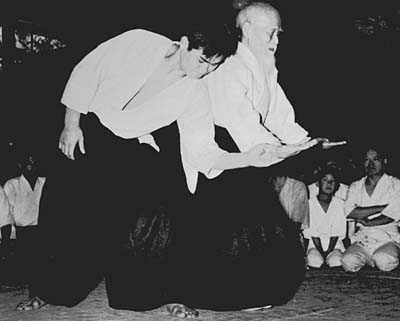

Although there appear to be differences in the approach to kata between Aikido and other arts, the mastery of kata still carries substantial weight in our study. It might, therefore, be helpful to describe the three progressive stages that appear in the study of the traditional arts that exist in Japan. Some of these I will illustrate with the hope that visualization will help the reader grasp them more fully!

Stages in the Study of Traditional Art

The first stage is known as shu, and can be translated as follows: to protect, defend, guard, obey, keep, observe, abide by, stick to, be true to. From these definitions, the characteristics of this particular stage can be said to be: protection (by teaching), observation (of teaching), keeping one’s eyes open (on the teaching.)

As one can see, there are two factors: one a subjective issue, the other objective. For example, to be protected (by the teaching), to be defended (by the teaching), and to be guarded (by the teaching) all refer to defense against external negative influences, and from falling into danger and making mistakes. These are all objective issues. On the other hand, to obey the order (of the teaching), to observe (the teaching), to stick (to the teaching), to be true (to the teaching), are all subjective, internal issues.

Technically, what is characteristic of this stage is the learning and embodiment of the fundamentals through the repetition of kata, exactly as they are presented, without the imposition of will, opinion, or judgment, but with total openness and modesty.

This is an important basic conditioning period both physically and mentally, wherein all the necessary conditions are carefully prepared for the next stage. Physically, this is the time when various parts of the body are trained — joints, muscles, bones, overall posture, how to set the lower part of the body centered around the midsection, the use of gravity and its control, the balanced use of hands and footwork, etc.

Mentally, one learns how to focus and concentrate attention on any particular part of the body at any given time, how to generate internal energy and its natural flow through the use of the power of the imagination. Furthermore, one learns faith, trust, respect, endurance, modesty, sacrifice, and courage, all of which are considered to be virtues of udo.

There is no set time or period to this stage. It all depends on the strength, quality, ability, and capability on the parts of both teacher and student. Generally speaking, however, it does not have to be too long, say from three to five years. Needless to say, this is said on the assumption that one trains earnestly, trains every day, and makes training the first priority of that time of one’s life.

The stage that follows shu is known as ha. The definition of ha translates as: to tear up, rip, rend, break, crush, destroy, violate, transgress, open, burst

As these definitions indicate, this is a rather dynamic stage in character and strongly leans toward negativity and denial. However, paradoxically this negativity leads progressively to self-affirmation.

The stage of shu, described before, is centered on the denial of individualism. That which then develops afterwards is a stage of self-affirmation, which is based on denial of the first stage, shu. A new horizon then opens up. It requires a totally different perception in order to grasp the whole meaning of what is happening at this time.

This stage demands careful preparation by both teacher and student. The strength of the teaching and deep insight and recognition of the potential of the student by the teacher, and the ceaseless and earnest study carried out by the student in response to the teaching, are essential. This is not a superficial self-assertion or pose of individualism, because its strength comes from having been through the flame of self-denial.

Technically, this is also the stage when it is required to rearrange or reconstruct what the teacher has taught. This includes the elimination of what is undesirable, unnecessary or unsuitable and allows new elements to be brought into the study as food for growth. These changes are based on the true recognition of self, together with accompanying conditions such as temperament, personality, style, age, sex, weight, height and body strength.

This is the stage, spiritually or mentally, when it is necessary to have a high mind of inquiry and self-reflection. More than anything else, it is required to attain a true and unshakable understanding of oneself as an individual. In other words, it’s necessary to have a clear vision of one’s own potential and the best possible way to stimulate it. This might require that one abandons or denies that which is already an asset or strength in one’s art. In this stage, in particular, gaining does not necessarily mean being creative, but often means losing or abandoning, and this plays an important part in the process. It is indeed a difficult task to carry out and one often does not see its necessity due to lack of true insight and courage.

Due to human nature, it is indeed difficult to deny what one already has, especially when it’s considered to be a good part of one’s possession. This is where most people get stuck and cease to grow. It is a matter of insight and perception in relation to the true recognition of self. In relation to human growth, this stage is still the period of the infant and youth and therefore still comes under the wing of the teaching and the teacher. Another, very significant part of this stage, is moving from the complete passivity of the previous stage to active responsibility for one’s own training.

What happens in this stage is that the one who gives (on the part of teaching — an external effect) and the one who receives (on the part of the student — an internal effort) simultaneously contribute towards the birth of individualism. It is exactly like the moment when the baby bird within the egg begins to break the shell from the inside as the parent bird helps to break through from the outside. If the time is not mature, the death of the bird results.

Again, there is no set time or period for how long this stage takes. However, this is an important transitional period. Grow from infant-youth to a complete, fully grown individual appears only after this stage.

The final stage is known as ri. The definition of the character is: separation, leave, depart (from), release, set free, detach.

As the definition indicates, this is the time of graduation. The completion of one’s study is here, though it isn’t the end of study. In this stage, one is given recognition as a Master of the art, as well as recognition as a complete individual, independent in the art. Obviously, in this stage, one has to acquire every required technical skill, knowledge and experience, and a dauntless personality. Spiritually or mentally one no longer depends or relies upon external help or guidance. One depends upon one’s own continual inquiry. This is the stage where one may begin to see the Mind of No-Mind, or the Sword of No-Mind, through an as-yet misty horizon.

Needless to say, to attain this stage takes work and study that is beyond expression in words. This is where one liberates the self from external reliances, including one’s teacher, until cosmic consciousness, the Mind of No-Mind and the Sword of No-Sword, are revealed. And it is the state of shoshin with its continuous growth that is the key to its attainment.

I’ve given a brief description of shu, ha, and ri with their progressive development and structure. However, these three stages do not necessarily set up in mechanical form with clear boundaries between them, although their progression and transformation are basically acknowledged through a certificate given by the teacher.

Referring the above system to the present ranking system practiced in today’s Aikido, the stage of shu is applicable up to the rank of third Dan, the stage of ha up to fifth Dan, and the stage of ri to sixth Dan and above. Obviously it doesn’t apply to everyone’s rank, for both negative and positive reasons. The quality of rank is often questionable; and then there is the genius, someone who is not necessarily restrained by any system.

One who has attained the stage of ri is considered to be a master of the art. He/she has become one of the successors of the Path who stands as the embodiment of the art to all others. Obviously, one is still regarded as junior to one’s teacher within the line of transmission. Nevertheless, one is equal to any other master, including one’s own teacher, in responsibility to continue to transmit the art to others. And by this continual transmission of responsibility the art develops through further generations.

Whether the above-mentioned system is still practiced in today’s Aikido in Japan, or whether it is workable here in the United States where culture, life-style, and way of thinking are so different, is not my present interest. I am convinced, however, that this system still carries profound value for today’s society, as it presents deep insight into the growth of humankind. Furthermore, it clarifies the responsibilities of the teacher and the student, thus contributing to the establishment of an ideal relationship between the two.

Whatever changes American Aikido makes in the future, it will still require a close association with Japan. This is not limited to the technical level, but is meant more broadly from a cultural perspective. Culture exists as an undercurrent within the art wherein knowledge, wisdom, experience, and insight with regard to human growth through physical and spiritual training can be found.

Seeing all change as creative development is a dangerous concept, especially when this is given affirmative recognition based on the superficial assertion of one’s own creativity. Equally dangerous is the harsh demand for independence of the art based on political or racial reasons, or giving too strong an emphasis on the differences between two countries (East is East, West is West . . . is an extreme attitude). This is important, especially as American Aikido as a whole is still considered to be in its youth.

Change is unavoidable and only natural. However, it is illogical to think only of change while not recognizing those things which do not change. Changes derive from differences. Their counterpart — no-change — comes from something common and unified between the differences, through which the value of the art becomes a universal asset or property of mankind.

Whether one places importance on a part that changes or on a part that does not change, it’s necessary to have a delicate balance. Ultimately, it is shoshin which will bring about both a deeper insight and a sense of balance.

In the final analysis, it is perhaps shoshin that American Aikido as a whole needs, to be truly creative and independent in the future.