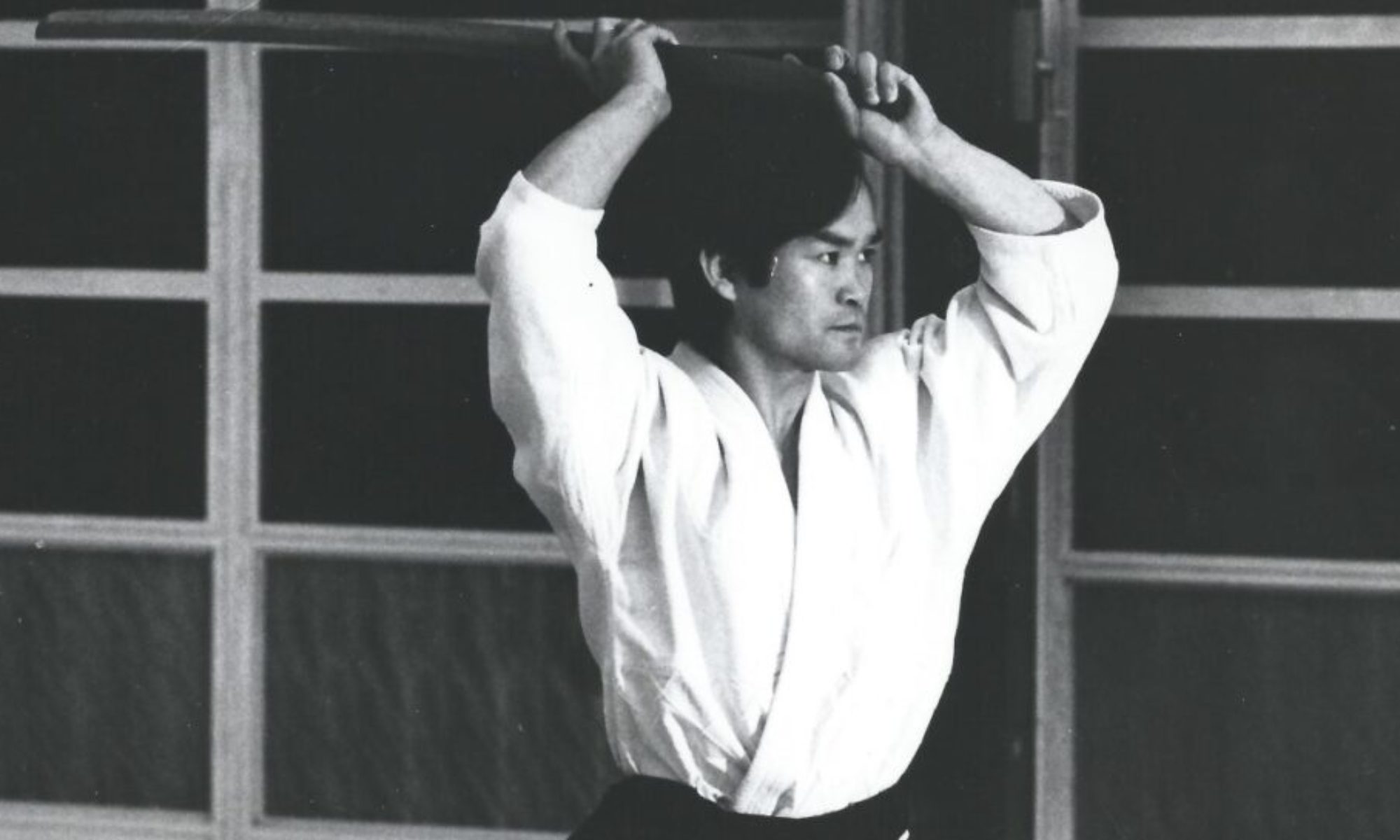

Galen David, East Lake Aikido

Chiba Sensei made an outsized impact on many people who continued on to dedicate their lives to sharing this practice. As is often the case in the wake of a charismatic leader, now nearly a decade after his death, I think the question of what makes a Birankai teacher distinct is both timely and difficult to answer. On the surface the senior Birankai teachers’ aikido remains unified by a technical coherence demanded of them by their teacher in their own training. The teachers in the organization I have come to know personally seem steadfast in the face of the tremendous changes that continually buffet us from the world outside of the dojo, and I admire them each for their unique ability to share the specific ways they were each shaped by their teacher.

Beneath the surface each brings the totality of their life experience to the endeavor–perhaps another facet of Sensei’s legacy. These senior teachers are also tasked with bringing forward the next generations of teachers who will, as a matter of course, be that much further removed from direct contact with Chiba Sensei. As a younger teacher, and new to this organization, I do not always know what it means to me to be a teacher, but my emerging sense of what it means is that we should be able to cultivate an active process of discovery in ourselves and our students. How else can we both adhere to the form as it has been transmitted, to a way of practicing that is equal parts encouraging and demanding, while also recreating it each time a new student walks in the door?

We are tasked with protecting the forms. We stand for that. We’re not content with our current understanding, application—we’re committed to staying engaged, committed to puzzling out more each time we step on the mat. Each strike. This grab. One more fall, and then another. We do not leave ourselves at the edge of the mat when we arrive at the dojo; we bring ourselves into our practice, fully, and as teachers we must be capable of holding this complexity while developing the eyes to see how each student beside us on the mat can move deeper into their own practice.

In some concrete way the responsibilities of a teacher to the student seem primarily concerned with the Shu stage of training. While the development that takes place in Ha and Ri certainly requires the guidance and support of a teacher, they also increasingly entail breaking away from and then reconciling the foundation developed in Shu. The challenges faced by students in this initial task are as unique and numerous as the students themselves. Additionally, these stages are themselves abstractions, idealizations that no two students move through the same just as no one arrives at the dojo with the same needs, strengths and liabilities in their practice. There is a model of teaching where one sets out to profess what they have learned. At its worst this is a simple imposition on students, at best it preserves something that was once of value but has become stale and dusty with the passage of time. There is another model, animated by the teacher’s own active process of discovery—a way of sharing knowledge that delivers content while also demonstrating a way to approach learning.

The teachers I have connected with in Birankai, while generous with their stories about the past and the deep and meaningful impressions left by their teacher, seem in their instruction to be sharing with me discoveries that are fresh and alive in their own practices. I also feel supported by them in continuing my own discovery both as a student and as a novice teacher. It is in this spirit, as conduit for depth and discovery, that I feel at home bowing-in between the students and the shomen, preserving and transmitting this pathway of self-discovery and beyond, ready for the students who come looking.

Students come to and access this practice in all manner of ways, for all types of reasons. For a little while or a long time. As teachers I believe we are responsible for cultivating depth in our own practices that moves beyond superficial inquiry. It is up to us to never be satisfied by the aha moments in which we “get “something, but to remain ready to chew and reflect on the moments we don’t get—the opening that comes and goes before we can act, the student that we missed, or the ease with which another brand new student picks up something it took us 20 years to find. It is a commitment to keeping a tradition alive, living, not complacent with our own knowledge or present understanding, while adhering to the spirit laid out by those who have come before us.

We must study the old, and find our way.

Editor’s note: this article was the author’s fukushidoin test essay. The assigned topic was “What qualities, other than technical excellence, should a Birankai teacher be expected to cultivate, and why?”

<3