This is an interesting interview of Chiba Sensei (by Stan Pranin) that was recently posted in the Aikido Journal.

By STANLEY PRANIN

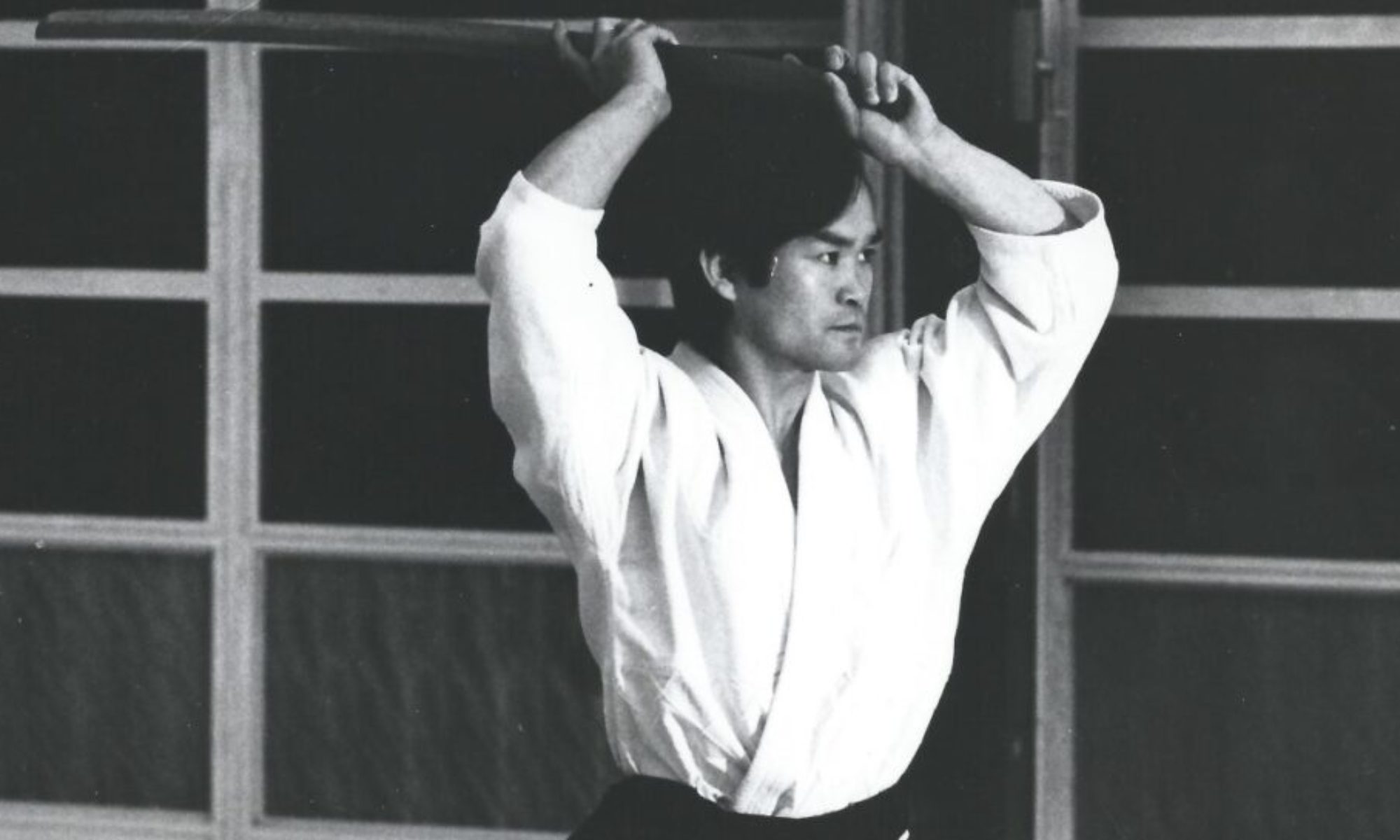

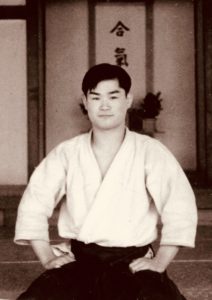

A Historical Interview with Kazuo Chiba Shihan

(February 5, 1940 – June 5, 2015)

As a young man of eighteen, Kazuo Chiba took one look at a photograph of Morihei Ueshiba in a book and knew that his search for a true master of budo had ended. Now 8th dan and chief instructor at the San Diego Aikikai, Chiba recounts episodes from his years as an uchideshi, and provides a detailed explanation of the concept of shu-ha-ri, as well as explaining his own view of the modern aikido world.

Aikido Journal: Sensei, I understand that you began martial arts with judo and later switched to aikido. Perhaps you could tell us about the way things were in those days?

Kazuo Chiba: Well, I liked budo quite a bit, especially judo. One day I happened to find myself in a situation where I had to fight a match with one of my seniors who was a nidan. He was a fine person who had taught me quite a bit about judo ever since I first entered the dojo, and he had been good to me in matters outside the dojo as well. He had a small body but he did marvelous judo, and could throw larger opponents without using any power. He used a lot of taiotoshi (body drop) and yokosutemi (side sacrifice) throws of a caliber you don’t see much anymore. He was very fast, too. He used to beat me all the time, but then…………..

To read the full article click on the link https://aikidojournal.com/2004/04/26/interview-with-kazuo-chiba-1/

Biran Online wishes to thank Josh Gold Sensei for graciously giving permission to excerpt and link to the Aikido Journal.