The following first appeared in the Summer 2012 print edition of Biran, the Aikido Journal of Birankai North America.

Most uchideshi, or live-in Aikido students, leave San Diego Aikikai with only lots of memories, sore joints and worn-out hakamas. But Edward Burke of South Africa left with notes for a memoir, The Sword Master’s Apprentice: Or How a Broken Nose, a Shaman, and a Little Light Dusting May Point the Way to Enlightenment.

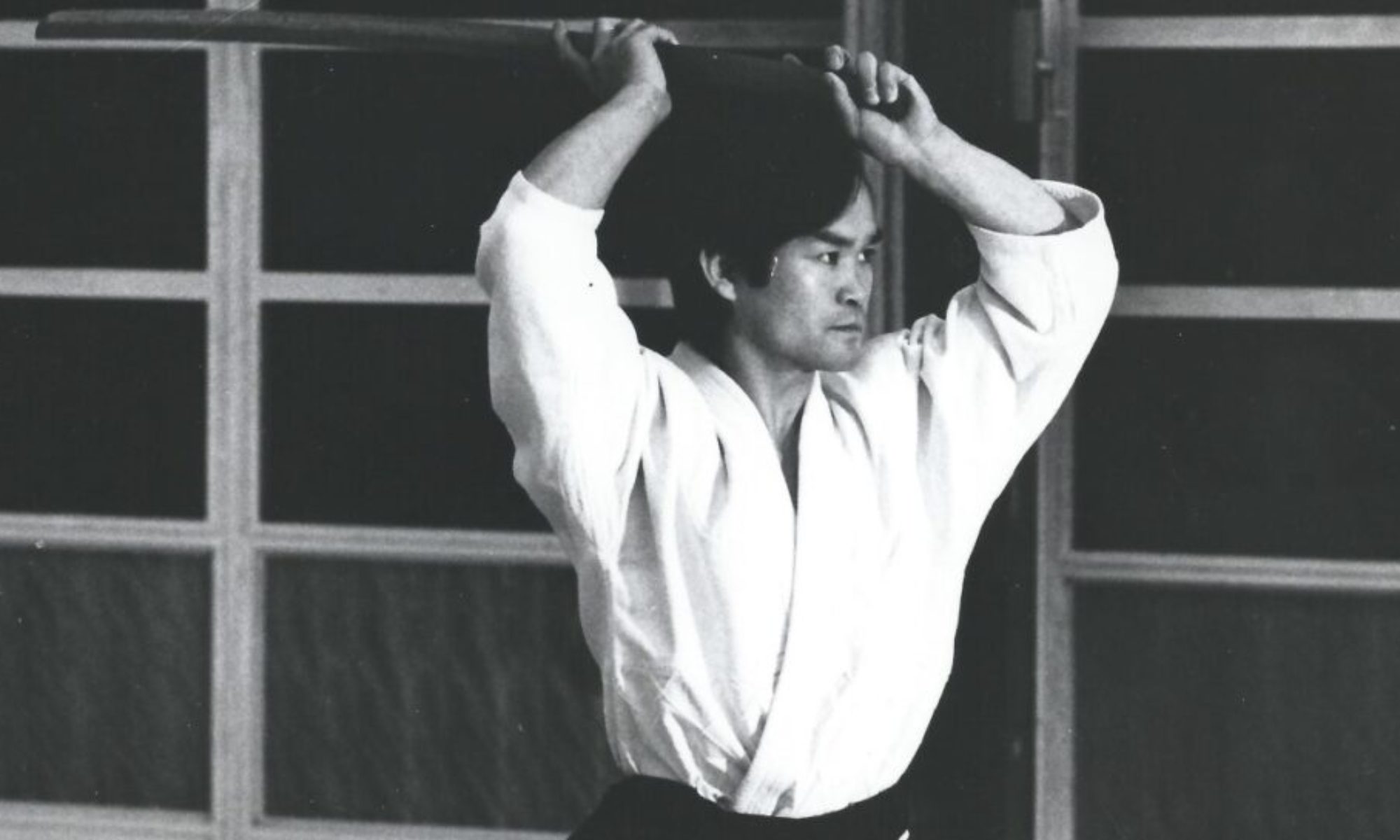

Burke’s book was published in 2012 and stirred lots of interest in the Birankai community. Burke lived at San Diego Aikikai for three months as a direct student of T.K. Chiba Shihan.

Starting with a vivid description of getting your butt kicked in class, the book relates the shock of a self-described yuppie’s rude introduction to serious Aikido training. Burke doesn’t sugar-coat aspects of the uchideshi experience, from the sufferings of an unwilling conscript to the agonies of morning class after a long night of enforced socializing. Burke was interviewed via email in June 2012.

Were you keeping a diary or some kind of journal as you were serving your uchideshi time?

I did keep a journal, but was not always very consistent about it. I took some detailed notes about both events and techniques, but at times I’d go for a week or two without  writing, just jotting down interesting things — perhaps something that Sensei said — on a scrap of paper to capture later. But when I sat down later and pulled everything into a timeline, I was really surprised at how much I could pull out of my memory. We rarely have the time or motivation to take a stretch of time, lay everything out in order, and fill in the blanks, and it turns out that one can piece a lot together that way. By the end I was a little worried that after spending so much time on these things in my head that I may be telling my own story rather than what actually happened, but fortunately people who were there, who have read it, seemed to think that it was a fair representation of the events.

writing, just jotting down interesting things — perhaps something that Sensei said — on a scrap of paper to capture later. But when I sat down later and pulled everything into a timeline, I was really surprised at how much I could pull out of my memory. We rarely have the time or motivation to take a stretch of time, lay everything out in order, and fill in the blanks, and it turns out that one can piece a lot together that way. By the end I was a little worried that after spending so much time on these things in my head that I may be telling my own story rather than what actually happened, but fortunately people who were there, who have read it, seemed to think that it was a fair representation of the events.

Were there experiences you decided not to include, and why?

In recounting my experiences in the book I tried to tell a compelling story which was accurate and also honest to the people who I wrote about.

On the whole, the story told itself, once I had decided what kind of story I wanted to tell. I was more interested in the human elements of the story than in writing a technical book for aikidoka – not that I am at all qualified to write a technical book anyway!

In crafting the story I did have to structure it a little to keep the narrative going, and inevitably I had to leave out quite a few little anecdotes just because they didn’t really fit the story. In particular I spent a few months of my trip in Latin America and had a great deal of fun writing up some of the crazy things that happened there, but I ended up cutting much of it out because it just didn’t fit.

In writing about real people (many of whom were my friends or teachers), respecting their confidence was a serious concern for me. I was determined to keep true to their characters and the events, so I didn’t pull punches, but I also tried to be sensitive and avoided repeating things said to me in confidence, especially hearsay and second-hand information. A major exception to this was Chiba Sensei. Sensei’s character loomed large in his dojo, and still does in Birankai more generally, and a certain mythology has built up around him. So the stories of Chiba Sensei, and the way people perceive him, are themselves an important part of my story.

Did your role as an observer ever clash with your role as a participant in the program?

Not really. I didn’t have a role as an observer — I was there to train, not to report on it. And I don’t think Chiba Sensei or anyone else would have put up with me skiving off to write up my notes. All that came later, when I had a few months to spare after my travels and thought — “Yup, I think I can write something worthwhile out of all this.”

Would you recommend an uchideshi experience to serious Aikido students?

Most definitely. I’m not all that good at multitasking and I find that if I spend concerted, focused time on anything my development is faster and deeper. I don’t think I’m alone in this. But also, training aikido is only part of being uchideshi. Training as uchideshi is an opportunity to learn about oneself, to hone all aspects of one’s personal practice, and to learn about running a dojo in the traditional way. There is no longer an uchideshi program at San Diego Aikikai, but there are still places where students can train in the traditional way. Since leaving San Diego I have visited Brooklyn Aikikai, for example, and spent some time there as uchideshi. I think what Robert Savoca Sensei is doing there is very special. Very demanding, it’s not for everyone, but his dojo has a very pure spirit, driven by Robert’s personality.

How has the response been to the book from Aikido people vs. non Aikido people?

The response has generally been very good from both sides. I wrote the book to be read by non-aikidoka, and in South Africa, where the book was released first, I’ve been fortunate enough to get quite a few reviews and interviews and people seem to get something out of it. (You can find some reviews on my Facebook page.) If the book generates some interest in aikido and brings a few students into dojos I’ll be very happy.

The responses of Aikido practitioners have also been positive so far, but I’ll leave that to Biran readers to decide for themselves!

The Sword Master’s Apprentice (Netsuke Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0987016904) is available as an e-book or in paperback at Amazon.com.