The Practice is the Purpose

The first time I met Boyet Sensei he was wearing a black, rabbit felt hat with a wide brim and no decoration other than a simple black band chasing around the crown. A bold yet natural choice for the cold weather of Vancouver BC in February 2017.

Attending his seminar at Mountain Coast Aikikai caused my practice to shift. Until then, I was practicing the techniques being taught. A beginner working at the surface.

My eyes absorbed, my mind decoded and my body moved.

What I found in Boyet Sensei’s teaching was essential, direct and fluid. A bold simplicity that resonated with my creative values.

“You do not have time” he said while we worked through a shomen bokken technique. He emphasized how important one, clear movement was in meeting the attack of an opponent’s weapon.

“You will be dead,” he finished, underscoring that speed was a matter of timing and reduction to essential movement. It was not a matter of more, but rather less.

His lesson was simple; nine words, one clear meaning. It catalyzed my Aikido practice with new perspective because he taught through the language of my creative values. I left the dojo in Vancouver excited to put the weekend’s learnings to daily practice.

It had triggered the shift, but the avalanche was still to come.

A year later, March 2018, Portland was emerging from winter’s slumbering rhythm. A bouquet of purple tulips rested with a wild, natural gesture on the kamiza at Multnomah Aikikai. Boyet Sensei was in town to teach a seminar at my home dojo.

I had just come off a rather taxing period in my career that ended abruptly. I was feeling listless and disinterested creatively. A problem for a designer and perfect timing for the kind of provocation a mentor can inspire.

I spent the whole weekend on the tatami, eager to absorb all the Aikido I could. To my surprise, what I learned illuminated a path beyond the dojo and helped to reignite my dimming passion for design.

Once again, Boyet Sensei was direct in his practice. No fluffy stuff, no extra movement; all practicality, applied simply.

A year before I was encountering all of it for the first time; I was just happy to get a signal. This time, I was tuning into the finer lessons that come with familiarity.

“Copy from someone better than you until you have made it your own, then find another person.” He lectured between techniques.

I thought about all the senior students and instructors I had learned from. Gweyn’s ukemi, Bill’s kokyu-ho, Thoms Sensei’s tenchinage. But had I committed myself to it? Had I owned my practice? Had I possessed my creative identity?

“You do not have time” he said about the little extra movements he was trying to prune out of his students. Once again, those five words echoed the clear message that changed my mindset a year prior.

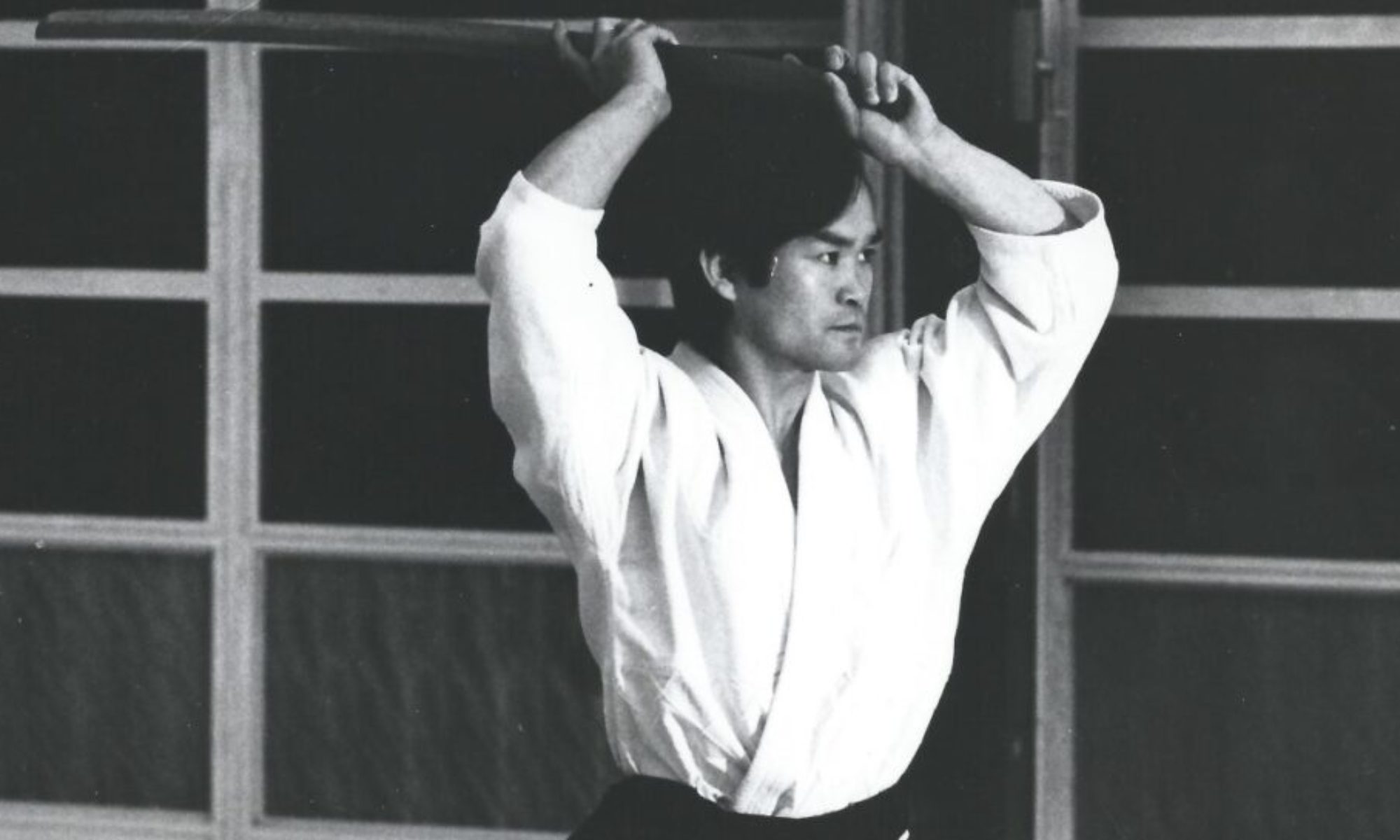

The way that Boyet Sensei demonstrated techniques struck like a bolt of lightning. Just enter, turn, and there it is; Ikkyo. The clarity of movement leaves nothing mysterious, and the reduction reveals beauty.

He spoke in familiar language.

“You must be beautiful, and to be beautiful, it must be simple.” Boyet Sensei explained during the Sunday morning Iaido class. “it may take fifteen, twenty years, but if you train, you will find it.”

In the creative arts, it is no different. Form follows function. Less is more. But getting there is a messy exercise with a lot of wasted movement. Out of the process emerges the value.

Boyet Sensei reminded me that the practice is the purpose. Beauty will come.

This is a lesson every creative from Dietre Rams to Paul Motian and the Eames have tried to pass on. Owning one’s way of being, their “do” is born in practice. Beauty is a result, not a destination.

Boyet Sensei had connected my Aikido practice with my creative values. His teaching changed the way I do both. It guided me below the surface and gave me a deeper perspective of my Aikido journey. It made my practice personal and I felt recommitted.

I try to remind myself to find the simple path and follow it boldly. In ikkyo or in life.

Rob Darmour is a 5th kyu member of Multnomah Aikikai. This essay first appeared in the Multnomah Aikikai blog; click the link to see the original and view a brief montage of Boyet Sensei practicing Iaido by Sam Brimhall.

More newly posted clips of Boyet Sensei can be found at the Birankai Aikido Video Channel on Youtube: