Carl Yuho Baldini

The old zen master said, “Now, you cannot see the compassion of your teacher, but in time you will.” These were the words of Ven. Genki Takabayashi Roshi spoken to our group of serious Aikido students. He was referring to Taiwa Kazuo Chiba Sensei who took us to an 8-day intensive zen experience (Rohatsu sesshin) in Seattle, Washington’s Kitsap Peninsula. Throughout those days we sat in zen meditation all day and until late at night, straining the limits of capacity and digging deep into the root of our nature. Chiba Sensei insisted that his personal students who were in the Kenshusei teacher development program attend intensive zen training to temper themselves and understand the core of their being.

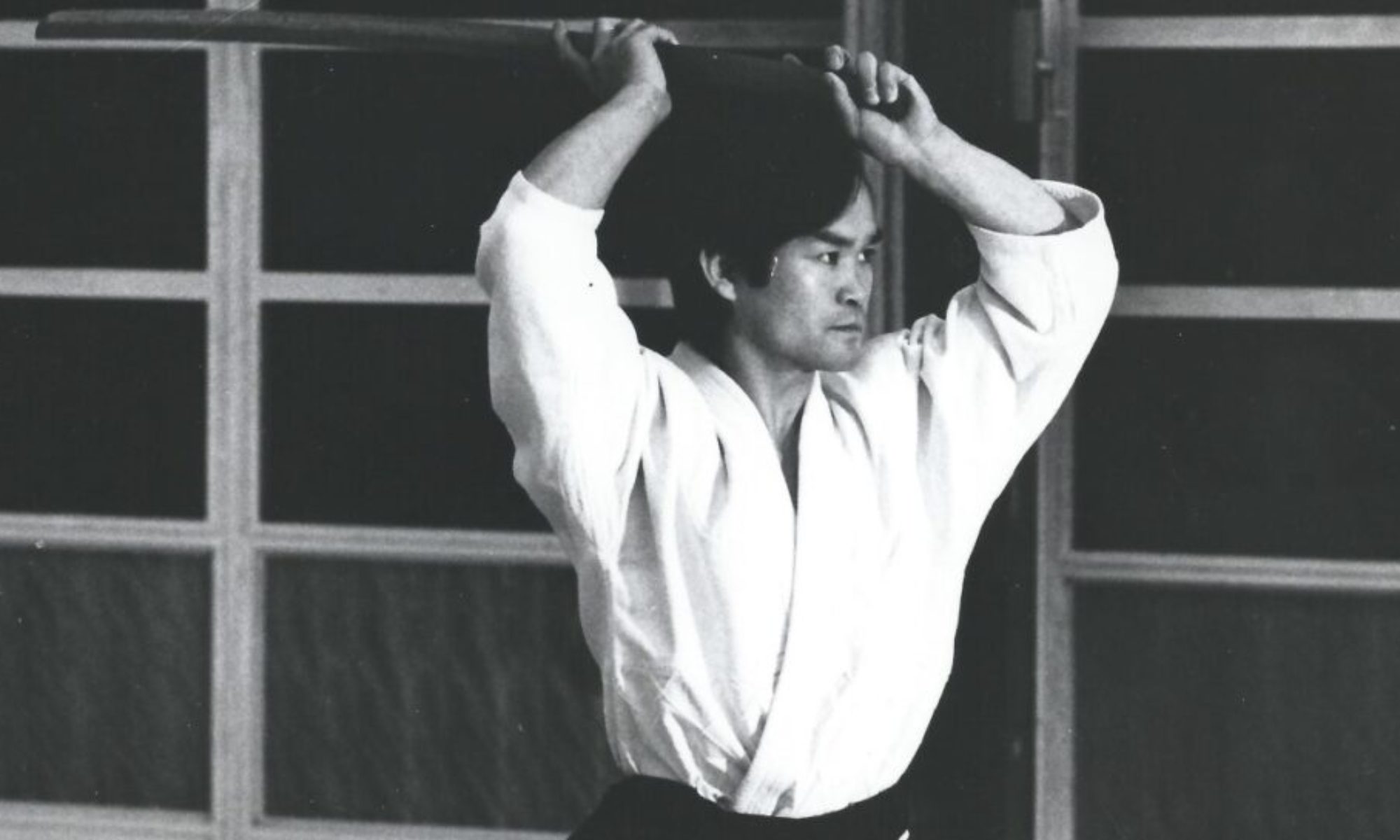

Chiba Sensei was a ferocious martial artist and a severe teacher to his serious students. In the Aikido community, he was famous for his power, tenacity, intensity of technique, and martial spirit. He was also known to have a fiery temperament.

For four years, I lived in close contact with Sensei as a kenshusei student. Of course, I attended his classes and was uke (demonstration student) for him constantly in the dojo and at seminars. I assisted him in the dojo wherever I could by caring for the junior students, cleaning, or any other task that I could tend to. I also spent many evenings after class with him and the other serious students.

When Genki Roshi said, “Right now, you cannot see the compassion of your teacher, but in time you will” the words resonated within me. Intuitively I knew that although I already was familiar with Chiba Sensei’s compassionate side, I knew that I would understand more deeply in the future. At that moment, I did not know that I would also understand Chiba Sensei’s generosity as a teacher, devotion to those whom he cared for, his deep commitment to Aikido, and his constant self-reflection.

I will share the story of my first personal contact with Chiba Sensei in the Fairmount Avenue Dojo of San Diego Aikikai. Although I was a beginner in Aikido, I had been practicing other martial arts seriously for over a decade. On the dojo schedule, zen practice was listed, “with permission of the chief instructor.” During an advanced class that was in progress, I inquired at the office how I should ask for permission to attend the zen meditation session. Mr. Hugo Harada, who faithfully tended the office said, “Go sit on the edge of the mat, and when Sensei walks off, ask permission.” I did as I thought was recommended. I chose to sit in the formal Japanese sitting position on the wooden floor on my knees with a straight spine with rapt attention observing class. As an experienced martial artist, (although truly an unknown at San Diego Aikikai), I believed that this was appropriate.

During the class, Chiba Sensei seemed to just stroll off of the mat, wandering into the vestibule apparently in contemplation of something. He walked past me and turned his back and was about 5 feet away. I thought that this was the perfect chance to ask my question. I stood up and went into the vestibule area and started, “Excuse me, Sensei…” As I opened my mouth to speak, Chiba Sensei whirled around and closed the gap between us like lightning. Inches away from me with fiery eyes flashing, he roared, “Where you from!” I answered with humility, almost stammering, “I am a beginner here, Sensei. I want to do zazen.” Instantly, Chiba Sensei’s countenance changed and he became like a pool of calm water. “Oh. Go get changed. And don’t sit on the wood like that. It’s not good for your knees.”

After the evening ended, I reflected on this, my first encounter with Chiba Sensei. I believe that Sensei, not knowing who I was, seeing me sitting as a martial artist, wanted to give me an opportunity to attack him, if that was my intention. He walked off the mat and offered his back as an opening if I desired it. Seeing that I did not intend to challenge but to sincerely learn, he sent me straight to prepare, even making sure that I would not hurt my knees. I share this story because it reveals so much about Chiba Sensei. In a flash I was able to see his intensity, martial understanding, and even kindness.

Sensei’s fiery martial presence and power are easy to point to because the stories are so dramatic. There are also many examples to share regarding Chiba Sensei’s generosity as a teacher, kindness, care, compassion, and self-reflection. Sensei demonstrated kindnesses quietly and without seeking recognition.

For a time in San Diego Aikikai, Chiba Sensei taught the children’s class, twice a week. Class was a serious affair for those kids fortunate enough to have Chiba Sensei for a teacher. One student, Matthew, had a physical disability. His feet were turned in and he had difficulty walking. Every single class Sensei took a few minutes with him to give him a type of “physical therapy.” He would gently stretch, rotate and massage the young boy’s ankles. The physical actions were clearly expert. Sensei knew what he was doing. However, I was more deeply impressed with the warmth and compassion that Sensei showed. Sensei tended to this young boy’s needs to ease his suffering and to help him be able to do the basics of Aikido with everyone else. I felt that this gesture, which he made every class, poured forth from Sensei’s heart.

In his daily teaching of adults, while not as gentle, Chiba Sensei was extraordinarily generous. He always did his best to ensure that students learned. He took great care to observe his students and determine which points he needed to address to ensure that they understood the concepts and made progress. At the same time, he ensured that the class’ intensity level was high so that everyone could experience the enthusiastic and energizing spirit of Aikido. Having traveled and seen many masters teaching, I have never seen a teacher make such efforts anywhere else.

If one was a serious student of Chiba Sensei, he was committed to the student’s development and generous at a higher level. The program for such serious students was to have him or her endure severe training in order to strip away preconceived notions and purify mind and body (misogi). This type of training required an environment that had an element of danger, with the initiate being pushed to their limits in order to have breakthrough experiences. Severity, discipline, and exhaustion was part of the process to allow the emergence of a natural consciousness and action response in alignment with Aikido’s universal principals. This was considered essential to being able to embody the art of Aikido and transmit the art in the future to others.

Sensei approached each kenshusei student in an individualized manner, tailoring his approach to each person’s needs in the program. It was tough because one was expected to put forth full effort at all times and expectations were very high. If you weren’t perceiving the lesson or not doing your duties properly, Sensei’s anger and consequences could be severe. Nevertheless, Sensei took in many students over time that had psychological, physical, or financial difficulties. When I was in San Diego, he used a mixture of discipline and kindness to help them find their way.

While many are familiar with the intensity and anger that Sensei displayed when displeased with his students, most people do not know how much care, concern, and worry he felt for them. For example, sometimes, he would ask me to take special care of specific students in the dojo. He wanted to make sure that, as much as possible, they would be able to not only endure, but to succeed in the severe training. He spoke to me privately, expressed his concerns, and gave me instructions to help and look out for them to ensure that they were successful. When he spoke, I felt the worry in his heart. It came through in his voice. I am sure that Sensei was very concerned about all of his students. As I was a young kenshusei, Sensei did not share his worries about all students with me. But I am sure that he had intense concerns for others as well. Furthermore, I am sure that Sensei’s devotion to the dojo and his students was a sacrifice felt by his family. The time and energy put into training was not without a price for Sensei’s wife, Mrs. Chiba, and their children.

In the first three and a half years I spent with Chiba Sensei, I was able to watch his self-reflection and efforts to make positive changes. He knew that the fiery countenance that was so useful in martial arts and training was damaging when uncontrolled or focused in the wrong manner. Sensei was keenly aware of his own battle with anger and had regrets when someone was hurt by him. When Sensei’s beloved student, Paul Sylvain Sensei, and his daughter Chloe passed suddenly in a tragic accident, Sensei’s heart was broken and he suffered greatly. Confronting the loss of someone whom he perceived to be so strong and talented, Sensei experienced a situation in which he embraced the fragility of life and the preciousness of human relationships which are always fleeting and short-lived, no matter how long they last. Upon Sylvain Sensei’s passing, I witnessed what I believe was Sensei immediately making efforts to change his interactions with others to become more gentle and patient.

Once, when we were at an intensive zen retreat together, Sensei was experiencing tremendous pain due to old injuries. I was trying to help by gently treating him with traditional healing arts. After a while, Sensei expressed his appreciation for the treatment. He also shared his concern that I shouldn’t use too much energy to help him because I would need it for my own training. Then he paused and with a serious and reflective tone said, “I have pain because I have given pain to so many others. It’s my karma.” I am sure that not only his body, but that his heart ached, too.

Eventually, I moved away from San Diego to live in Japan. After about a year, I returned home to visit. Sensei received me joyfully and warmly. Leaning on the railing outside San Diego Aikikai on a warm evening, Sensei left an opening, a “suki,” for me just as he did the first time that I met him. However, this opening was different. Instead of an attack, he left an opening for a question. I felt that at that moment I could ask anything. I turned to Sensei and said, “I have trained for years now in Aikido, Zen, and Misogi, but sometimes, I still feel fear…” Sensei smiled while lightly shaking his head and replied, “There is no answer for that. No matter how good you are, there is always someone stronger than you… What really matters is how you live your daily life. That is what is most important.”

I came to Chiba Sensei seeking his guidance to achieve his strength, martial skill, and intense concentration and energy. For thirty years, I have reflected on his teachings and I marvel at his commitment to others, his compassion, his self-reflection, and his devotion. I came to Sensei hoping to be a stronger martial artist, but as I live with his example in my heart, I am inspired to simply strive to be a human being who takes correct action in the service of others the best that he can. When I think of Chiba Sensei, this quote from Buddhist monk Ven. Thich Nhat Hanh comes to mind:

“Someone who has the capacity to go back to himself and listen to his own suffering and look deeply into his suffering…. He will be able to understand that suffering inside of him that carries with it the suffering of his father, his mother, his ancestors… and getting in touch with suffering inside will help you to understand your own suffering. And understanding suffering will rise to compassion. And when compassion rises you suffer less right away…”

Chiba Sensei was a warrior-teacher who worked with all his might to transmit Aikido to his students. He suffered greatly in many ways during his journey, more than can be described in this essay. I believe that he did look deeply inside of himself at his own suffering and his own actions over the years. Perhaps because of this, he was able to help many seekers to find the Great Path. As he is remembered for his contributions to Aikido, I hope that he will also be remembered for his commitment to others, his self-reflection, and for his compassion.

Y.C. Baldini Sensei began his Aikido study as a personal student of T.K Chiba Sensei in 1995. He has trained in the United States and Japan in the disciplines of Zen and Misogi. Baldini Sensei is a practitioner of Qigong Healing Therapy under the personal guidance of Master FaXiang Hou. He teaches at Aikido of Manorville.