By Sanders Anderson, Multnomah Aikikai

A lot of things go through your mind when test time rolls into your life. Even more so if you happen to be someone with the misfortune of failing your previous test. Beyond the obvious considerations of assessing one’s skill, is perhaps an even more daunting survey of a student’s determination. For me beyond the technical requirements of passing or not passing, is the question of whether or not the fire is lit. Is my flame a mere flicker or is it sufficiently hot enough to do its job? Can it heat the contents and transfer energy with mind, body, and spirit integrated as one?

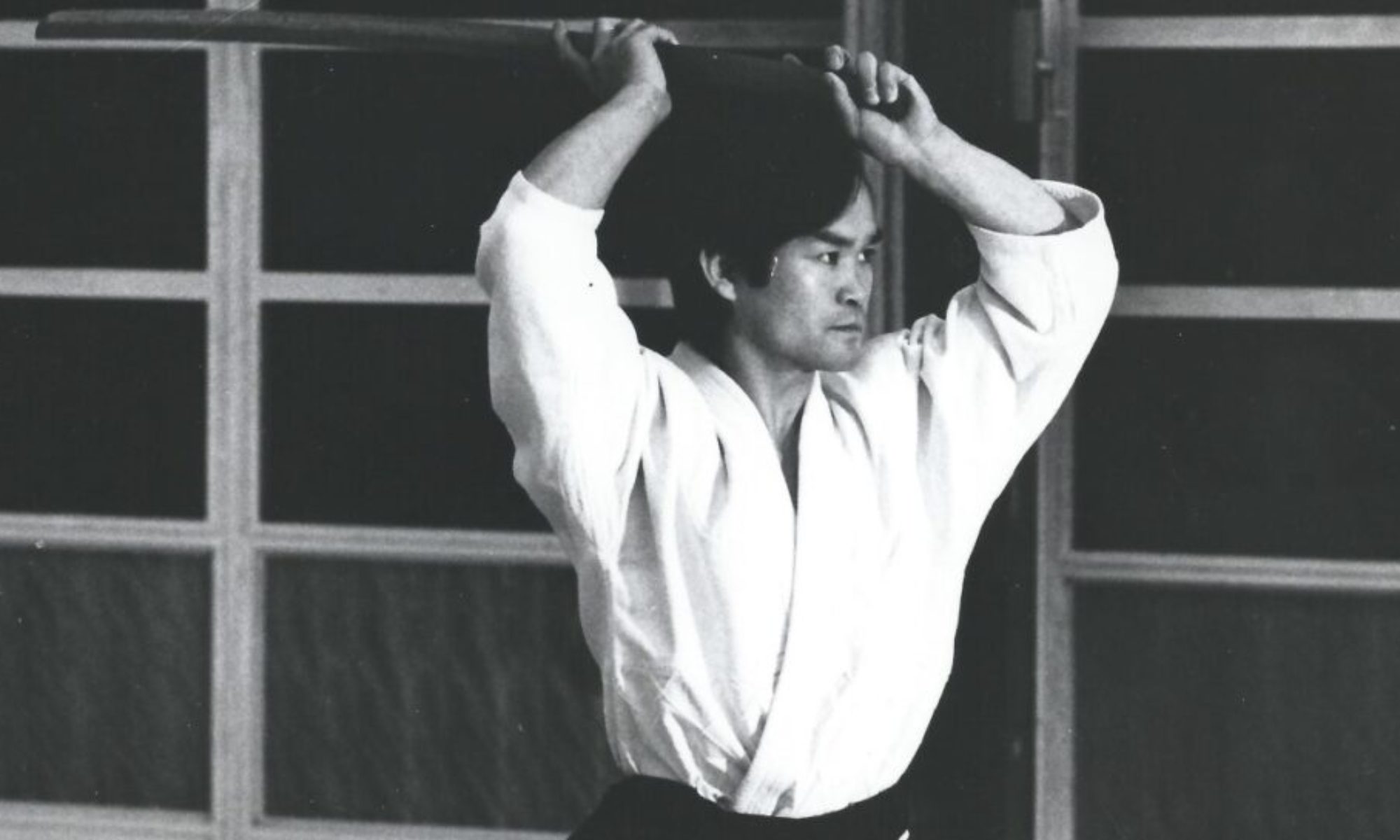

I had a lot riding on this test for the rank of 1st kyu (level/grade) in the Japanese martial art of Aikido. I really wanted to show I had spent significantly more time on the foundations of our art: hanmi (stance) and taisabaki (footwork). I also wanted to prove to myself that I had been willing to eat the bitter fruit, spending the requisite time alone outside of class, continuing to forge my will, and bringing those developments to the dojo. My hope was that others would bear witness to my progress.

Three nights of testing sounded like a good idea at the time as a welcome switch up to the usual program of having to prove yourself on a single night. This allowed myself, and others, I believe, to be less anxious about getting it all right (like such a thing was even possible). The test format proved to be physically taxing with one to two hours of testing every night for three consecutive nights, Tuesday through Thursday. Wednesday, as hump day, will forever have a new meaning for me. In summary, I feel it was more demanding physically, but less so mentally, since the one-chance-is-all-you-got pressure was mitigated by expanding the format into three days.

I even had a strategy. Or at least I thought I did. Rather than rush through the techniques with the nerves of a cattle bell, I would try to relax into a moderate pace and get into the groove, my groove, whatever that was. I needed to create my own stepping stones on this path to 1st kyu. I was naked, alone, and exposed. No further preparation could help me at that point. I relied on what had helped me most in all manner of challenges – positive mental attitude. This was something I could do. I just needed to focus my concentration.

Fleshler Shihan told me once: “This mat is just as much yours as anybody else’s. You need to own it.” I felt as if I was incapable of owning the entire area of the mat but surely I could attempt to own a small patch of it. That much I could do.

Unfortunately, after what felt like a near brilliant first night of demonstrating strong foundation level skills, things began to fall apart for me on the second night. Where did my basics go? Where did my confidence go? They didn’t tell me they were leaving. And suddenly I felt abandoned. Now missing both, I was feeling uneasy to say the least, and with a certain anticipatory grief for how this would all end up. I remember telling myself I just had to get through this and live another day. Perhaps my resilience would return the following night.

The third and final night of testing I felt like I got my groove back. I got the fire back I and turned up the heat. Even when I was caught off guard with tantodori (knife defense techniques) and jyodori (techniques against staff attacks) I remained as placid as a lake. It might not have looked that way on the outside but that’s what I was aiming for on the inside. I wasn’t exactly sure how I would express myself but I knew I had to be in control. I would embrace the circumstances as guests, and invite them in as if I was looking forward to seeing them. I wasn’t necessarily proud of my specific responses, but I was very proud of the resolve I displayed in the face of simulated threats.

There was also a certain ugliness and ego I experienced during testing. I began making odd comparisons between myself and others. “If you can do better than him you will pass.” Ultimately I had to let these comparisons go. No one could take this test for me. And comparing myself to someone else was not only a waste of time, but energy as well. Whatever basic level of body mechanics and integration I had attained, now was the time to show it. Winning had no resonance here, only existing in the moment as it presented itself.

“When one is under sound attack

one must die, and yet live,

from moment to moment.

It is in momentary living

that one is free from distraction…”

–– Thomas M. White

As the test results were called I sat on the floor in seiza (proper sitting) with dreaded apprehension. Was I good enough and were my techniques sharp enough? Regardless of the pending result, I felt some degree of my personal development was evident for all to see. What I did not expect, in my quest to attain the rank of 1st kyu, was to be elevated instead to the rank of shodan (black belt). In fact, upon hearing the results called, my eyes nearly popped out of my head. The handshakes and congratulatory gestures would have a significantly larger context now. Unexpected? Absolutely. In addition, it was a particularly special honor for me because I am one of the first shodans to be promoted by chief instructor Van Amburgh Sensei.

What does shodan mean for me? It means so much. I was so proud of this achievement and the perseverance it took to get to here. This was a 14 year journey of blood, sweat, and tears, both figuratively and literally. I only wish my mom was still alive to share this achievement with me. For three weeks after testing I felt like I was floating in the clouds. Now I could finally go to yudansha (black belt) class and feel I belonged there.

What I wasn’t ready for was a mild sense of shame or embarrassment coupled with a case of post-goal blues. Why couldn’t I just be happy with the present moment and simply bask in this glorious warm sunshine? These are answers I still don’t have. Maybe I was instinctively feeling that I had reached the top of a mountain fully unaware of the even higher mountain tops that lay directly behind it. Not only was the endeavor not over, it had just begun. In fact, shodan literally means “beginning degree”.

In regards to the technical aspects of our art, shodan means revisiting irimi (entering), tenkan (pivoting), taisabaki (footwork), and ikkyo (elbow control). Each has something I need to earnestly re-explore on a more intimate level. But more generally, shodan is a chance for me to begin weaving a tapestry with the basic elements of our art. Its pattern will only be revealed after jumping back into the forge, emptying my cup, and re-filling it anew with fresh insights from a beginners mind.

“The true warrior acquires the nature of a priest.

It is in the mind that the body is trained, and in

devotion that the mind is trained.” –– Thomas M. White

Shodan also means looking for ways to use Aikido in daily life. I recently delivered a design presentation to one of my clients. Just before that meeting my nerves were shot. This was a big account. So to raise my spirit, I bowed in (as if in Aikido class) in the hallway outside their office. After gathering my center, I stood up and then walked confidently into that meeting. The dojo’s boundaries are limited only by my own artifice and preconceptions.

There is also an opportunity to expand my definition of some basic Aikido concepts beyond the dynamic sphere of physical practice. For example, irimi (entering) could potentially mean finding space in my schedule and my heart to work at a soup kitchen. Or the idea of tenkan (pivoting) could mean making a dramatic shift in my previously held position to consider another way of seeing or looking at challenging circumstances in the world. Is it possible for me to be more compassionate towards others? Even someone I perceive as an opponent? Of course this is difficult but not entirely impossible.

“Be kind whenever possible.

It is always possible.”

–– His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama

And finally, shodan for me, means walking a spiritual path. This is what attracts me the most about the possibilities of the journey we share and infinitely more applicable. In fact, most of us are more likely to be in an automobile accident than a street altercation. Spirituality has the possibility to transcend the physical manifestations of our day to day life. I am fully aware that martial arts may not help me when faced with a periodontal surgeon or to deal with my trauma of being robbed as a youth in Los Angeles, but it can help me be more present. Here. Now. It can also help me shed the confines of the ego and the limitations it imposes on me. I’ve got some serious baggage. But I’m traveling lighter everyday, freeing myself from the unnecessary weights keeping me from swimming to that distant shore.

I dedicate this essay to all the teachers illuminating this path, both past and present. I sincerely feel that without their wisdom I would be nothing more than an empty shell, void of any base or structure: Sifu James Wing Woo, Shihan Thomas M. White, Shihan Albert Wilson, Shihan Nobu Iseri, Shihan Dennis Belt, Shihan Minoru Oshima, Sensei Nobu Arakawa, Shihan Aki Fleshler, Sensei Suzane Van Amburgh, Guro Albert Tabino, and Yangsi Rinpoche.