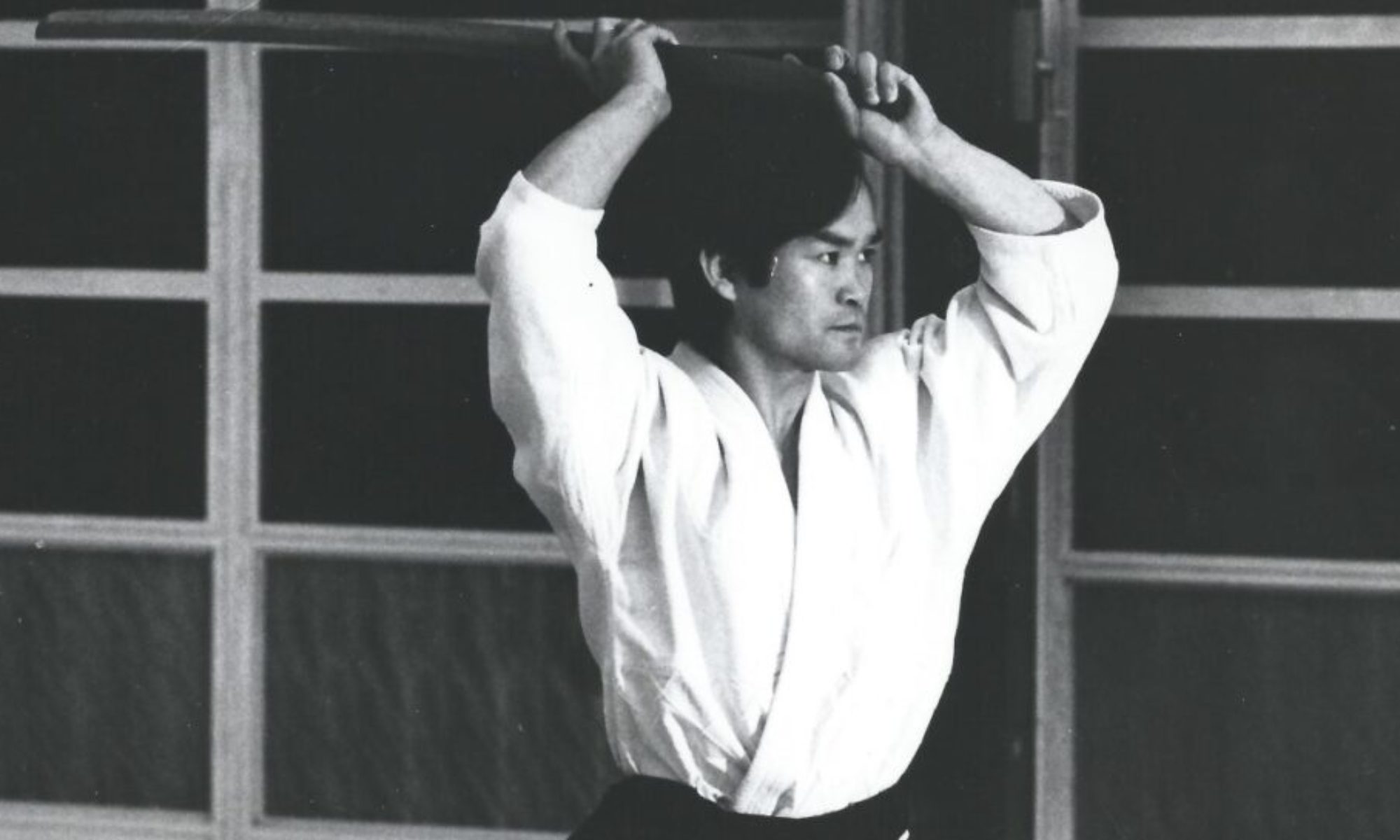

by Norine Longmire, Aikido Takayama

Recently my mother died relatively suddenly. The shock, anger, and sadness that accompanied the news and then the eventual acceptance of the reality of her death was overwhelming. Yet everything seemed to come into focus. Things that I thought mattered, I no longer tolerated; people who I thought would be in my life forever, are gone. When my mom was dying, all things including Aikido were dropped as if they were never a part of my life, nor mattered in the end. The act of swinging a wooden sword seemed pointless when the life of a mother so dear – I felt she was like my right arm – was draining painfully away.

Shutting one’s self away is one way to cope with death. It is what I did. I did not want to see anyone. Hearing the language people use around death was offensive to me. “I’m sorry for your loss.” (I did not lose my mother – she died!) “She’s in a better place.” (How do you know she is in a better place?) When I could not touch her, hug her, speak to her, or hear her voice I could not be around people saying these platitudes. Having others assert their own beliefs and faith on my experience caused even more suffering.

The sadness that remains after the death of a loved one can be like a pit that continues to get deeper and broader. Every day is a struggle to get out of bed, to face a world where we continue to kill each Continue reading “Living and Training through Heartache”