John Brinsley, Birankai Teachers’ Council Chair and Chief Instructor, Aikido Daiwa

June 5 marks the sixth anniversary of Chiba Sensei’s passing. While I was not his student, I was fortunate enough to train irregularly at the San Diego Aikikai for about three years. In his memory, here is a recounting of one weekend with this remarkable man.

In November 1961, O-Sensei and Kisshomaru Doshu gave a demonstration in Nagoya, Japan’s industrial heartland, to inaugurate the opening of the city’s first Aikido dojo. Hombu then dispatched 21-year-old Chiba Kazuo to be its first teacher.

The Tashiro Dojo was and is unusual because it jointly teaches Judo and Aikido. It was founded by Tashiro Keizan Sensei, a Judo 8th dan who became acquainted with O-Sensei and wanted his own students to learn Aikido. Chiba Sensei spent several months teaching there before returning to Tokyo, and in his wake other Hombu teachers were sent to Nagoya, including Kanai Sensei.

When Chiba Sensei moved back to Japan from the U.K. in 1976, he renewed ties with Tashiro Dojo. He taught a seminar there in 1979 and again several times in the mid-1980s after moving to San Diego. There is footage of him teaching in Nagoya during a trip he made with several of his San Diego students in 1986, with Juba Nour Sensei taking ukemi. The connection was such that several Tashiro Dojo students traveled to San Diego to practice on at least two occasions.

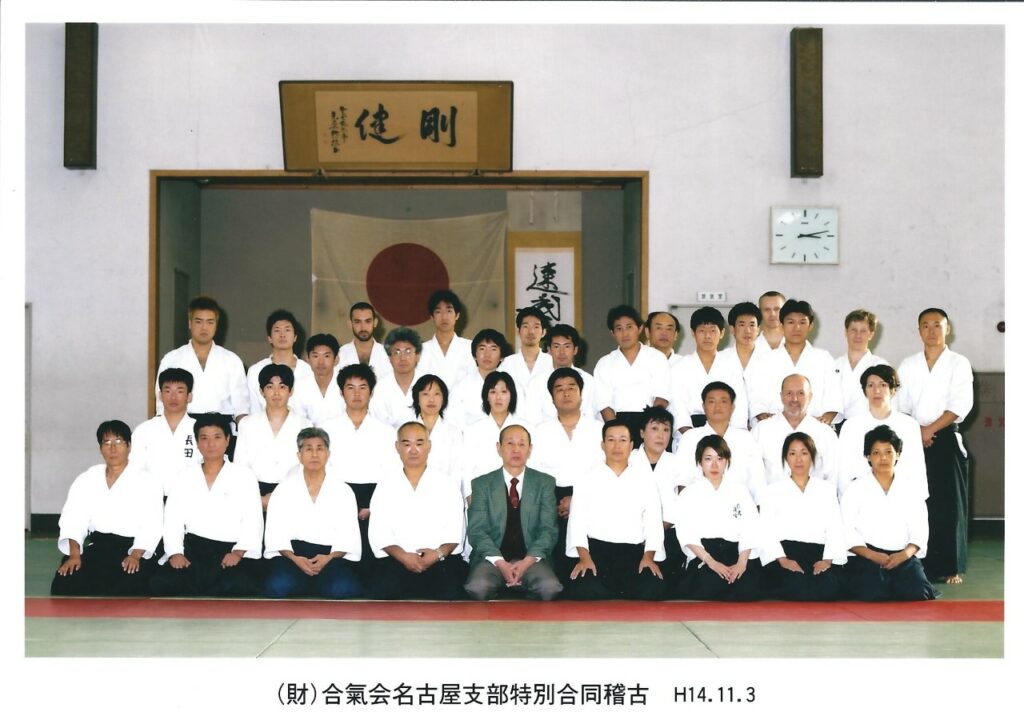

In November 2002, Chiba Sensei traveled to Nagoya to (belatedly) mark the 40th anniversary since he’d first taught there by giving a two-day seminar. I went down from Tokyo with Didier Boyet and a few others, including Miyamoto Sensei, who was only able to attend the Friday class. Also there were Murashige Teru and Robert Savoca, who had arrived from New York only a few hours earlier. We were warmly welcomed by Dojo-cho Wada Akira Sensei, now an 8th dan, who had begun Aikido under a very young Chiba Sensei.

Tashiro Dojo is old, musty and not large. There were probably 50 people on the tatami that night and another 10 either sitting or standing watching in street clothes, despite a complete lack of audience space. Not everyone had enough room to stretch out during Sensei’s warm-up. But once training started, it didn’t matter.

Most of the hour-and-a half keiko was suwariwaza. I had never seen Chiba Sensei teach in Japan before, and he was in his element. He practiced with his old students, taking ukemi as they exhausted themselves trying to move him, and was expansive in a way that was different from classes at the San Diego Aikikai or at seminars. He wore Robert and Teru out, however. Both of them had skin scraped off their shoulders from all the ikkyo ukemi, in part due to the hard tatami. Practice was in very close quarters, and the windows fogged up thanks to the steam. I got to train with Miyamoto Sensei and Wada Sensei, which was terrific. I remember looking over at Didier and seeing him grin as his partner struggled to throw him.

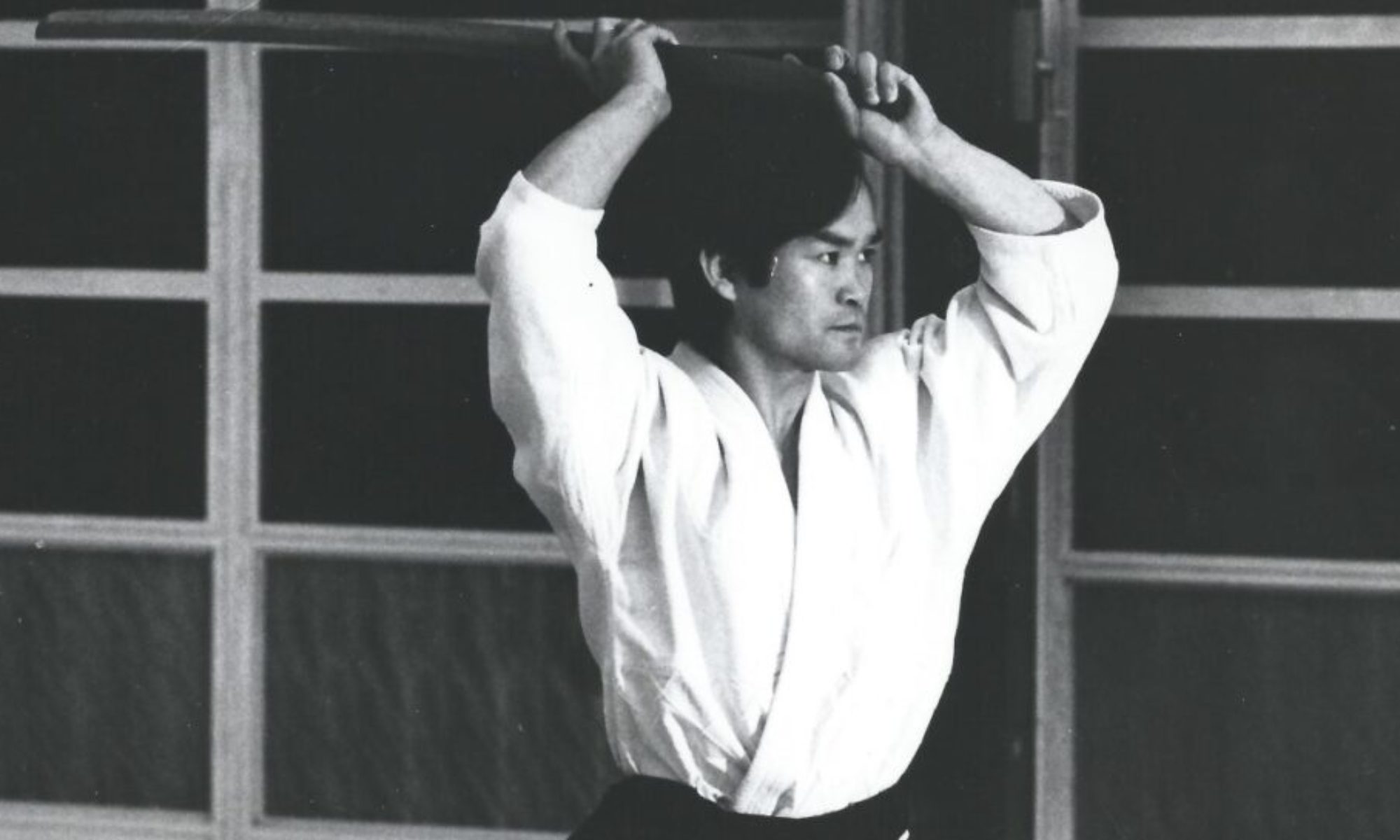

Saturday’s keiko was in the prefectural budo center (virtually every town of any size in Japan has at least one), a much bigger space. There were at least 100 people on the mat from various dojo. Chiba Sensei taught a body arts class, focusing on aihanmi, and then did some basic bokken waza, which was new for many of the participants. Once again, Robert and Teru shined in taking ukemi. Not everyone stuck around for the second part of the class.

Then Chiba Sensei gathered everyone and talked a bit about his youth and finding Aikido. Much of what he said – as far as I can remember – echoed remarks he’d made elsewhere, but one comment stuck. “All I really wanted was a place where I could sleep, eat and train eight hours a day,” he said. “Where I was very fortunate was that O-Sensei was there. I probably could have been happy doing Judo or Kendo, but he was the big difference.”

Saturday night, several of us accompanied Sensei to an onsen – a hot springs inn. Unless it’s for a romantic getaway, there are really only three things to do at an onsen: eat, bathe and drink. After arriving, we spent a long time in the bath, followed by a beer or two. Then we had a wonderful meal, which was probably served around 7 p.m. and lasted at most an hour or so. Which of course left the rest of the evening for two things: drinking and bathing. Did I mention drinking?

My roommates for the night were Didier, Robert, Teru and William Gillespie. My memory for some of this is hazy, but I’m pretty sure at one point either Sensei came to our room for a bit or we visited his. Either way it was nice. Things went downhill from there, particularly when the five roommates returned to the bath at some ungodly hour, and did drunken Sumo. A word of advice: never do drunken Sumo with Teru in a bath (or any other place). The long and short of it is I ended up with a nice purple eye, thanks to a blow to my face.

The next (same?) morning, looking and feeling very much the worse for wear, we straggled to the bath before breakfast. And despite our states at the time, Didier, Robert, and I all have strong memories of what we saw as we entered: Ishii-san, who had begun Aikido under Chiba Sensei four decades before as a teenager, washing Sensei’s back. Public bathing remains a strong part of Japanese culture, and it’s not uncommon for a younger person to wash an elder’s back. But seeing it then touched me deeply as a gesture of devotion.

It also recalled another episode in Sensei’s life. When Kisshomaru Doshu passed away, Chiba Sensei wrote a memorial in which he recounted how much Doshu had meant to him and the Aikido world. In it, he writes about how he quit Hombu in 1979 over some disagreements and went to live in the Japanese countryside. One day, without warning, Doshu arrived at the Chiba family’s home. The two men spent the night at an inn, where they shared a meal and a bath and Sensei washed Doshu’s back. “I believe he came to make sure I was all right,” Sensei wrote.

That struck me as I made my way behind Ishii-san and Chiba Sensei as silently as possible, and left me ruminating while nursing my head. And it stays with me as I think about the legacy Chiba Sensei left to his students and the dedication he inspired. I hope he rests in peace, secure in the knowledge that he touched a great many people, and in so doing changed their lives.

Learn more about Chiba Sensei’s life in Aikido with Power and Grace – Portrait of a Master: T.K. Chiba